In many ways, 1935 was a pivotal year. In February, my father was born in Princeton, New Jersey, at a time when it was hoped that the worst of the Great Depression was behind us. In November, Hans Muth was born in Brandenburg, Germany. Also, 1935 was an important year at BMW, where both the R12 and R17 models were introduced. In addition to carrying BMW into the future, they defined the look of Beemers for generations to come. It would take Muth ascension to change that in the 1970s.

The end of The Great Depression was unfortunately a prelude to war. In 1945, Muth and his sister watched as their mother was murdered by invading Soviet troops. They fled to what became West Germany into a sector controlled by American and British forces. Design concepts came early to young Muth, and he still speaks fondly of the American P-51 Mustangs arcing gracefully across the blue skies of Central Europe. Instead of weapons of war, they were elegant designs that stirred the soul.

During the Korean War, my father was an ace mechanic in a USAF Mustang squadron. His spirit was stirred by those same creations. The sound of a Packard Merlin engine remains a thing of wonder to this day.

Back in Europe, after WWII, Muth graduated from secondary school in Solingen as a trained toolmaker. Eventually he became a freelance graphic artist and designer. Muth initially worked in automotive advertising and trade press industries illustrating automobile catalogs for Porsche, Mercedes, Opel and VW.

He also drew design proposals for contemporary sports cars for the magazines of one of the largest and best-known publishing houses in Germany, the Motor Presse Verlag, Stuttgart. In 1965, he began his career as a designer at Ford of Germany and two years later he moved to Ford in the USA. Muth returned to Germany in 1968. Three years later, he switched to BMW to take on the responsibility for interior design.

And then motorcycle magic was struck. At about this time, BMW hired the American Bob Lutz to help shake off their stodgy image. Lutz was responsible for an array of advances at BMW, including the creation of the 2002 Turbo, the Motorsports division and M-cars. Later he masterminded such things as the creation of the Dodge Viper.

Before that, Muth found BMWs motorcycle designs stodgy and dated. No one seemed to be responsible for designs, so he volunteered himself into the role. Finding a willing partner in Lutz, who was focused on building a performance image, they forged a brilliant alliance. The first product of this collaboration became the truly iconic BMW R90S.

Introduced for the 1974 model year, this was a seismic shift for motorcycle design. Today it is hard to completely appreciate just how much was changed by Muth’s work. The R90S was audacious in design, in paint, and in prestige. It was incredibly expensive at the time and helped change the BMW Motorrad direction for decades to come. It was also a blast to ride.

Meanwhile, back in New Jersey, I was about to graduate from high school and my dad became entranced by the new BMW line. While an R90S was the object of affection, it was a more cost effective R90/6 that came home. Two years later I purchased my own Beemer, a “Toaster Tank” R60/5. Together we fueled a sense of adventure, an appreciation of great design, and broad discussions about the activities in Munich. Hans Muth was frequently discussed, but somewhat shrouded in mystery. Before the Internet era, it was difficult to dive deeply into subjects of interest. Muth was like the Michelangelo of Motorcycling.

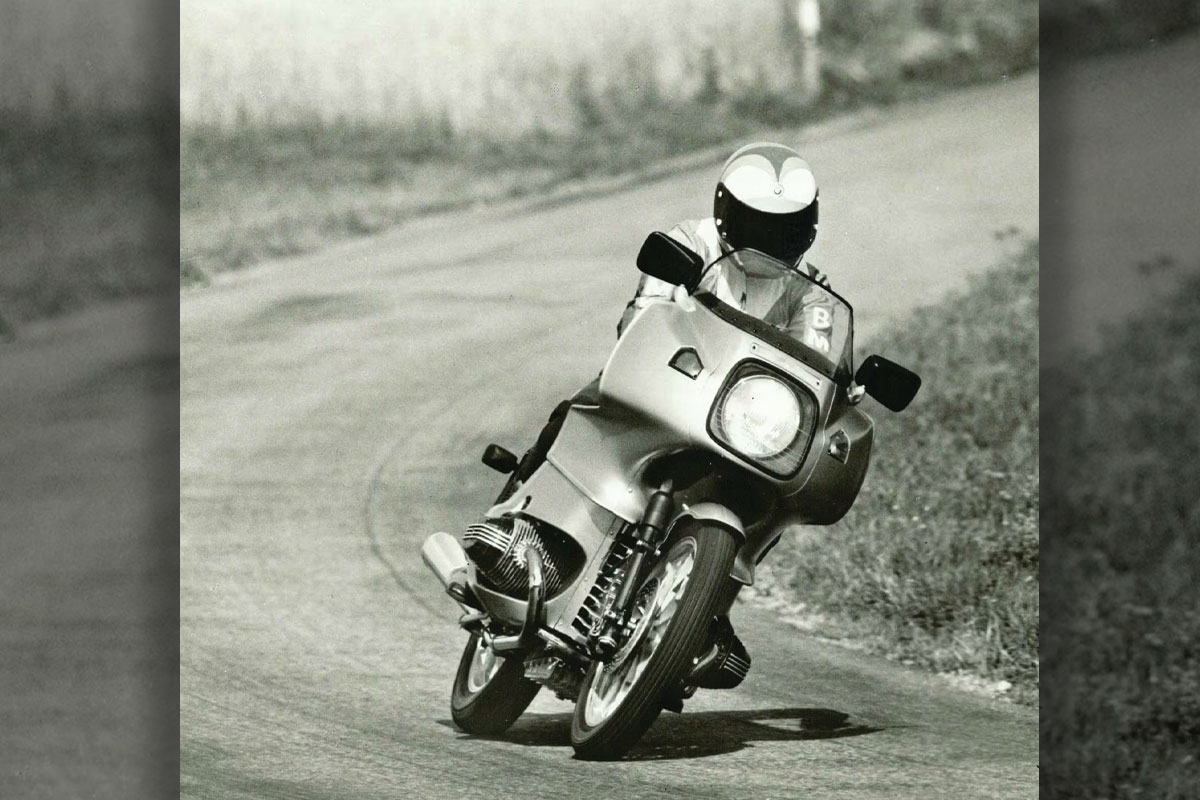

Muth’s genius, and the productivity fostered by the Lutz relationship, continued through a magical decade. The 1977 model year saw the introduction of the R100RS, the first motorcycle with a fairing to be wind tunnel tested. It remains an engineering tour de force almost half a century later.

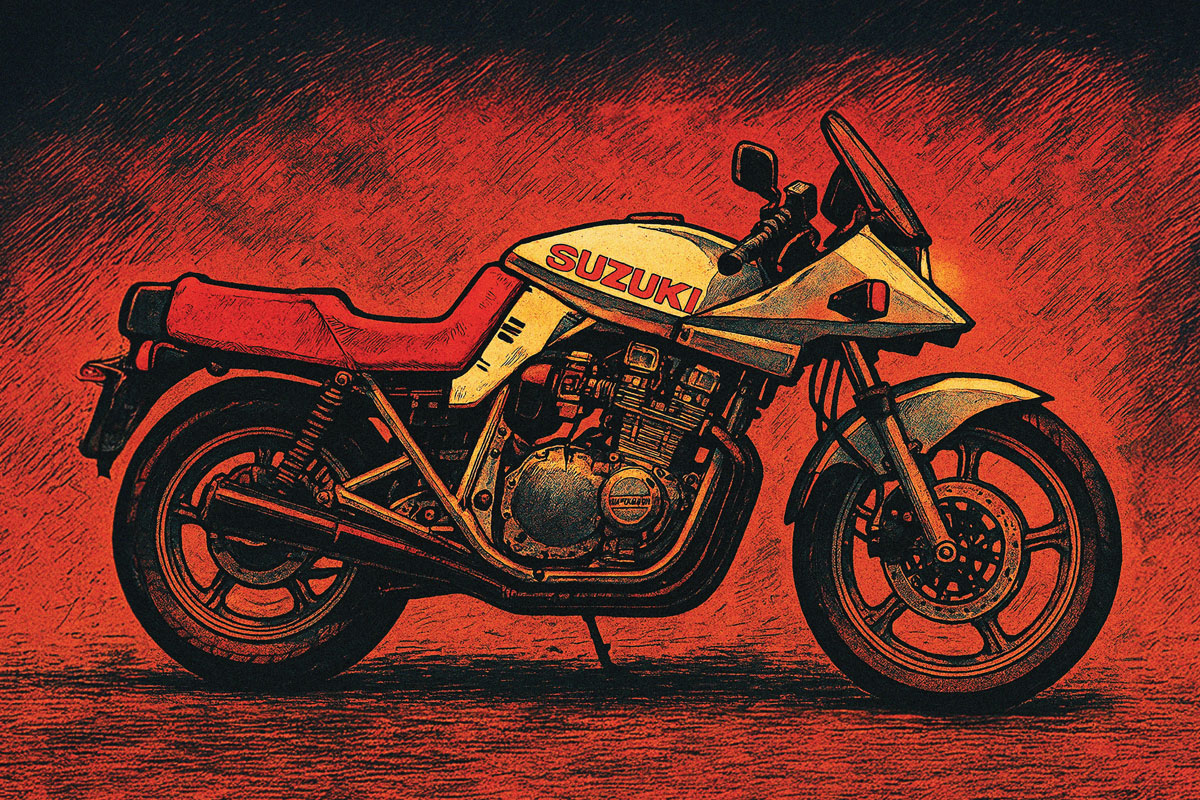

Muth oversaw the development of other bikes, including the R100RT, the R65LS, and the R80G/S. The latter opened the way to all modern adventure bikes irrespective of manufacturer. It’s a remarkable list of achievements. Later he went on to design the original Suzuki Katana and a stunning array of other vehicles and products.

I had the good fortune of meeting Hans shortly after acquiring a first year 1977 R100RS originally owned by Malcolm Forbes. Later, I managed to locate a 1974 R90S that matches what my own father and I admired years ago when both it and Muth were something of a mystery.

As part of the 100th anniversary of BMW motorcycles in 2023, I had the good fortune of working with Hans on a presentation he was to deliver in Pennsylvania. Sadly, poor health kept him home in Stuttgart at the time, but with his permission, I delivered his presentation. The symmetry of that opportunity was nearly perfect.

Even at 90 years young, Muth remains both active and with strong opinions. An essential component of good design, he believes, is that it should create experiences that delight the human senses. It should, of course, be a thing of cosmetic attraction. It should draw one in with a sensation that something meaningful and powerful could happen.

There’s also an elegance to design, which is inviting to the user. If this notion of elegant simplicity sounds Apple-like, it’s with good reason. Steve Jobs once kept his BMW motorcycle in the corporate lobby to both encourage and inspire his own designers.

Muth sees a user ultimately becoming an integral part of the resulting experience. With his designs, including both the R90S and R100RS, there’s a sense that you “wear” them more than “ride” them. That’s clearly intentional. They are gorgeous on their own but invite the user to be part of the adventure to come. When these were introduced there really were no direct competitors, although the world of sports-touring quickly took off from manufacturers everywhere.

When the R80G/S came along, it also created a whole new category of adventure motorcycling which today is the lifeblood of many manufacturers.

Usability is also key to design, and the ergonomics of the Muth era are terrific. Everything simply is located exactly where it should be for functionality. Later regulations forced standardization on motorcycle control layout, but the gear from the mid 1970s set a high watermark that is yet to be exceeded.

Of course, design style is one thing, but the proper color combinations are also critical to creating the overall experience. Muth was focused on the idea that BMW had a philosophy from the beginning that, “You could have any color you wanted so long as it was black.” Not entirely true since there were a few exceptions.

The R90S in its original Silver Smoke motif shattered that image, creating something unlike anything on the market in 1974. A year later, a Daytona Orange color option was added. This was the color of the racing bikes that stunned the world by winning the AMA Superbike Championship in 1976. S

Steve McLaughlin shocked the motorcycling community by winning the very first race of the season series, appropriately, at Daytona. It was another shot heard round the world. His teammate, Reg Pridmore, won the championship on a sister bike. In keeping with the long standing Bavarian reputation for durability, both of those race bikes remain with us today in operating condition.

Shortly after that the 1977 R100RS appeared in a silver blue garb that set a new standard for sophistication. These bikes appeared concurrently with the original Star Wars movie, and it looked like a machine that Luke Skywalker or Han Solo would have been comfortable piloting. Both the style and the color were quickly imitated by others.

Speaking of imitation, I once asked Muth if he’d done work for Moto Guzzi, given the development of both the SP and LeMans in the late 1970s. He smiled and said no. Then he noted that imitation is a great complement before describing them as “Bavarian Pizza.” Many machines from Kawasaki, Honda, Suzuki and beyond reflected the influence of Hans’ design genius.

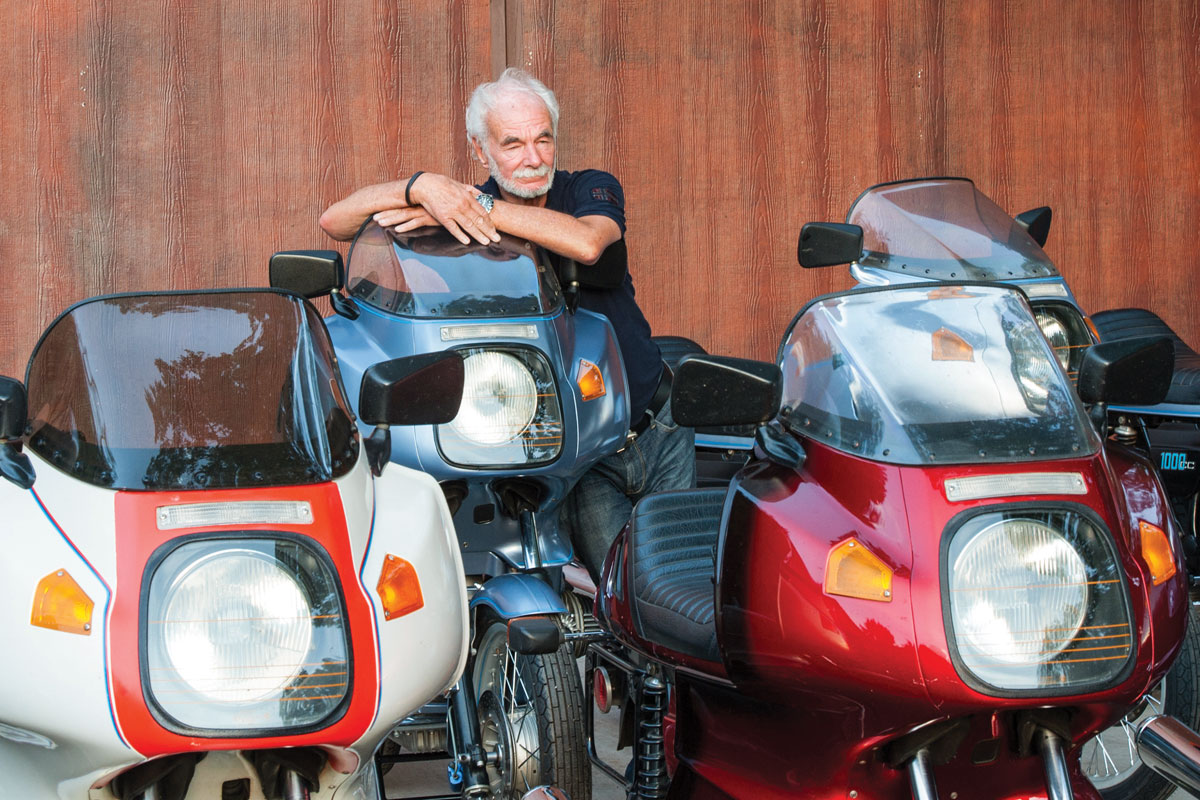

One of the things Muth truly appreciates today is the level of interest he finds from the motorcycling faithful around the world. He’s a regular guest at events across Europe, including museums that showcase his work around excellence in design. The BMW and Suzuki faithful are particularly engaged by the products he was associated with.

A reality now, of course, is that it has been more than 40 years since he left BMW and embarked on other adventures in different parts of the world. The fact that he has a loyal following, many of whom were born after he left the company, is a testimony to the timelessness of his work.

It is also probably not a great surprise that Muth isn’t a fan of much of the group-think design efforts that are being introduced to the market today. In some instances, there are copies of machines from an earlier era, where an effort is being made to introduce 50-year-old design themes onto modern frameworks. These generally fail to capture the spirit and the proportionality of the original efforts. In other instances, designs seem to have become so homogenized that without a logo it is impossible to tell one brand from another.

And, while the technology injected into modern machines is clearly impressive, the electronics and computers make the experience sterile and disengaging in ways that are a contrast to the well-conceived machines of an earlier era. As if to make the point for him, one manufacturer is now in a position where the electronic gas caps are failing, leaving riders unable to put fuel in their new $30,000 motorcycles.

In another instance, the driveshafts now need to be replaced as a “regularly serviced” item. As Hans noted, the term “better” is a hard one to define. Is it more important to have 0-60 mph times below 4 seconds, or a machine that with proper maintenance should be able to easily swallow more than a half a million miles?

BMW fans hope Muth will join the 50th anniversary celebration this year of the R100RS. He’s on board with the concept, although he said, “When you’re 90 years old, next Tuesday sounds like long-term planning.”