Spinning down through shafts of golden light filtering through the multi-colored leaves, I needed to gather speed for the next uphill rise. Ignition retarded slightly, throttle twisted fully closed, with my left heel depressing the clutch lever, I removed my left hand gingerly from the bars and felt for the tank mounted gear lever. Freewheeling in neutral, there was no time to lose as the bike began to slow, requiring a light twist of the throttle to better match engine and rear wheel speed, a firm pull on the gear lever, and up and away with my left foot. Simultaneously rolling back on the throttle, while leaning into the smooth right-hand bend, I’d done it! For the first time in two days I had made the perfect downshift. No primary drive chain snatch, no clutch lurch, no false neutral, just a pure, fluid series of actions as the bike purred through the Virginia countryside heading toward the next blind rise.

This was more than a decade ago, but I’ll never forget pulling out of Wheels Through Time Museum in Maggie Valley, N.C., on a well-worn 1956 Harley Davidson Panhead, it was a moment I thought would never arrive. Confused by the concept of using my left foot for clutch duties, my left hand for gear changing, and a throttle with no return springs, my hectic fumbling left me bathed in sweat, even though it was a cold fall morning. Ahead of me, headed toward the Blue Ridge Parkway for a couple of days riding, museum owner Dale Walksler was sitting comfortably on UX-3—a 1936 Harley Davidson that never existed.

To clarify the situation, it is necessary to go back to 1933. Indian had just introduced a new motorcycle featuring a re-circulating oil system. Harley, in public at least, was still promoting the “total loss” oil system by advertising that Harley Davidson’s used only fresh oil. And, while this was their public stance, behind closed doors this system was being developed. Installed in an 80-cubic-inch engine, the Motor Company stamped the cases UX to denote the experimental status. With the experiment a success, by 1936 the overhead-valve Model E Knucklehead was in production, complete with a re-circulating oil system.

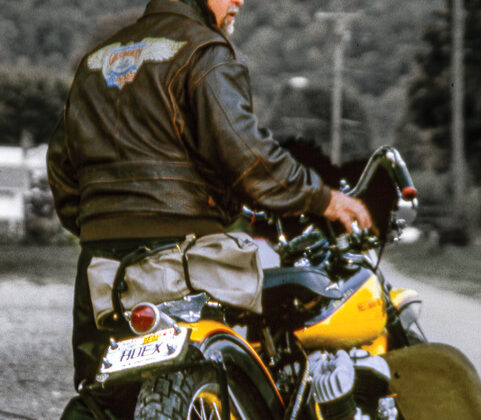

Fifty years later at a swap meet in Ohio, Walksler found himself rummaging through a box of parts. Uncovering some strange engine cases marked UX-3, and, knowing Harley Davidson never produced a motorcycle bearing these markings, he quickly snapped them up. Later he found UX-2 and combined the parts to build a complete engine that he put into a period 1937 rolling chassis. The bike soon made history when Dale entered it into the Great Race in 1995—the first serious motorcycle entry. Sponsored by Pennzoil and piloted by Wayne Stansfield, UX-3 finished an incredible fourth. (Relegated to sixth by a mathematical calculation that favors older vehicles.) It was as good as a win though, the bike performing flawlessly as it made its way from Ottawa, Canada, through America to Mexico City.

Back on the ‘56 Panhead, I successfully made it to the Blue Ridge Parkway where it was time to breath and relax my death-grip on the handlebars. Up ahead, Dale was enjoying the stunning mountain views. But, riding a vintage American motorcycle for the first time, there was no leaf-looking for me as we climbed to Waterrock Knob, visited the highest point on the Parkway and plunged down the mountainside toward Black Balsam.

I named the ’56 “Myrtle” for being slower than a turtle. Losing what little speed she was capable of, and vibrating like an out-of-control jackhammer, I pulled over at the first rest area. “Fouled plug” boomed Dale as he leapt off the ’36 and broke out the tool kit. With a new plug installed, Myrtle felt like she had been drinking pink gins at happy hour as we positively sprinted up the mountain.

A quick gas stop to top off the tanks, and it was time to get back on the road. Luckily, starting Myrtle was a breeze as there was no engine compression to impede the kick-starter’s progress. I just set the controls, gave her a little gas and kicked away. This resulted in a rattling, whirring, thumping sound, as her various mechanical parts attempted to coordinate themselves in time for the pistons to meet the firing spark plugs at top dead center. She would then give a few asthmatic coughs and wheezes, puff a little smoke, before settling into her imitation of the Home Depot paint shaker. But you had to love Myrtle. Rattling along behind the nearly see-through screen, bouncing on her hard-tail rear end, and squeaking up and down in the sprung saddle, every mile was a wonderful adventure.

But the real reason for our journey was for me to ride UX-3, and just before the Biltmore Estate came into view, Dale pulled over so we could trade bikes. Instantly feeling lithe, and low, the only problem was, the ’36 engine had some healthy compression. Thankfully, Dale noticed my vain attempts to get it started, and leaping off Myrtle had the engine purring with one vigorous kick. I was suitably humbled and eased down on the foot clutch before selecting first gear. Everything felt much tighter, and letting out the clutch, while twisting the throttle, the bike actually accelerated. Or at least it felt like it when compared to Myrtle’s gentle gathering of speed.

This quickly brought on a new problem as I entered a tight corner. Daydreaming about George Vanderbilt’s incredible 250-room home, the sound of scraping metal violently interrupted my peaceful thoughts as rushes of adrenaline shot through my veins. With senses suddenly in slow motion, I picked the bike up, got on the brakes and leaned it in again. More scraping, more braking, and right before an unwanted appointment with the barrier we made it through. Thankfully, this was the only heart-stopping incident, and, apart from a few embarrassing moments when I tried to pull away mistaking the front brake lever for the clutch, as it is located on the left handlebar, the rest of the ride was fairly stress free.

With my heart rate back to normal, and the ’36 loafing along on a whiff of throttle, it became necessary to make a sudden detour. Black skies were hurling small, pebble sized raindrops at us and we were forced to turn the bikes west into Virginia. Here, the small, twisting back roads tightened up as they headed deep into tobacco country, the sky returning to blue. Sat comfortably in the sprung saddle, modern aspirations began to melt, as soft green fields and hazy mountain views diluted the daily business of deadlines and distances. Friendly waves from slow moving pickup trucks and smiling faces at local diners became the norm.

And, deprogramming my usual riding habits, I slowed in time for corners, planned my gear changes well in advance and learned to deal with the old engine’s gentle power output. Cresting the rise, I slipped the bike back into fourth and throttled off before rolling down through the next series of corners. We were heading for home, but I was happy, as there was still a good way to go. Dale and I weren’t just traveling, we were traveling back through time, on a ’56 Panhead called Myrtle and a bike that never was.

Neale Bayly is an accomplished motorcycle adventurer rider, journalist, photographer and humanitarian. Read more about his travels at nealebaylyrides.net.

Editor’s note: Dale Walksler, founder and curator of Dale’s Wheels Through Time in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, died Feb. 3, after a long battle with cancer. As a remembrance, we offer our readers this article from noted motorcycle journalist Neale Bayly, who had the pleasure of riding some of the museum’s vintage Harleys with Dale several years ago. Many a visitor to Walksler’s museum enjoyed the experience of talking to him as he happily fired up a century-old motorcycle for his visitors. While the man has left us, his amazing collection of two-wheeled treasures awaits your next visit.