Nestled at the base of the Cumberland Mountains, the Devil’s Triangle awaits. It’s one of those motorcycling routes that will motivate you to rise at dawn and endure a couple of hours on the interstate just to savor this lonesome road’s dramatic twists.

A few years ago, a riding companion and I passed through these hills on my way north to the Cumberland Gap. We had little time to linger, but today this is the destination. One of my favorite aspects of motorcycle touring is the freedom to just stop at a wide spot along the road and listen to what the mountains whisper to me.

The Devil’s Triangle consists of three East Tennessee roads — routes 116, 330 and 62 — just northwest of Oak Ridge. It’s my third trip here, and I always traverse the triangle in a clockwise direction, which allows riders to tackle the curviest parts going uphill.

The western corner of the triangle borders Frozen Head State Park, a scenic natural area I decided to explore on this trip to the region. I roll into the park and dismount by the peaceful visitors center, a welcome rest stop after the long ride from home on the opposite slope of the Appalachian Mountains.

“The big draw is the Cumberland Mountains themselves — the hiking we have,” said Jacob Ingram, the park manager of Frozen Head State Park. “We’ve got 60 miles of hiking trails, various degrees of difficulty from easy hikes, half-mile or quarter mile in length to 10-plus if you add some together.”

Many of the park’s trails were constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. A fire tower at the top of one of the mountains offers stunning 360-degree views of the Cumberland Plateau.

“We have a lot of activities folks come to the park for, picnicking, camping. We have primitive day-use campground. People can come fish. We stock Flat Fork Creek here with trout in March and April,” Ingram said. “The hiking, getting away from everything busy in the world, getting in some of these remote areas and being able to enjoy it, that’s one of the big draws for us.”

I take a short motorcycle cruise through the park. Flat Fork Creek burbles peacefully and I stop along its banks often to take in the serene, wooded cove. Moss-covered rocks line the stream bed, and the sun sends streams of light rays through the towering trees.

“We are one of the last remaining wilderness areas in east Tennessee; 24,000 acres we protect here and manage. We’ve got 16 peaks over 3,000 feet. That’s where the namesake comes from — Frozen Head. The moisture in the air freezes to the outside of the trees above 3,000 feet, so the top of the mountain gives it a ‘frozen head’ appearance,” the park manager said.

The region once saw coal and timber industries harvesting the area’s natural resources before much of it was purchased by the state of Tennessee.

“We have a lot of different interpretive programs, historical programs,” Ingram said. “The CCC camp was here. We share a lot of commonalities with Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary because a lot of this land was purchased in the 1890s for the prison and later was handed over to the state forest.”

Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary, first established in 1896, operated until 2009. Today, it welcomes visitors with tours, a restaurant, distillery and gift shop. It’s best known as the prison from which Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassin James Earl Ray escaped in 1977. Ray covered 12 miles in the rugged mountain terrain before being captured nearly 55 hours later.

His capture so close to the prison prompted a couple of marathon runners to scoff that they could’ve covered a hundred miles in that time, inspiring The Barkley Marathons, an exclusive and eccentric ultramarathon where runners each spring tackle a roughly 20-mile loop in the state forest and prison grounds. Cross-country runners try to cover 100 miles in 60 hours. Only 15 runners have ever accomplished the feat since the course was extended from 55 miles to 100 in 1989.

For motorcyclists, the prison makes a great spot for picture taking and a rest stop before you begin the most challenging section of the Devil’s Triangle. The first turn after the prison begins an uphill climb along a twisting ribbon of two-lane. Traffic is light and I fall into that thrilling zone where bike and rider respond as one — jinba ittai, as the Japanese saying goes.

Since my last tour of this road, I notice erosion encroaching on the white line on the edge of the pavement. One small mistake here and a rider will find themselves tumbling down a steep mountainside. I poach closer to the centerline, knowing that has its dangers as well. Soon, I crest the first ridge and can relax a bit. In the distance, I spot one of the towering windmills of Buffalo Mountain Wind Farm. The Tennessee Valley Authority erected a total of 18 windmills on the mountaintop, although the three oldest were recently decommissioned. They can generate enough clean energy to power 2,000 homes, according to the TVA.

Not far after I reach the “peak” of the triangle and turn southeast, I become fascinated by the rock cuts along the road and pull over for one of my “zen moments in the mountains.” The geology of this region differs from my native Blue Ridge Mountains. The brown sedimentary sandstone, with a thin band of what looks like coal deposits, line the uphill portion of the road. It strikes me as so different from the gray granite and quartz rockfaces I’m used to seeing in the southeastern Blue Ridge Mountains. Geologists say the North Carolina side of the mountains were forced up from deep below when the continents collided millions of years ago.

A rider with a pillion buzzes past with a wave. It’s the first rider I’ve seen since leaving the suburbs of Oak Ridge. I’ve had this amazing road to myself for most of the day. A few miles ahead, I find them taking a break near a small creek tumbling down a cove and pull over to chat.

Faud Accawl, a bladesmith who once appeared on the History Channel’s “Forged in Fire,” was born in Beirut and grew up in nearby LaFollette.

His Kawasaki Versys 300 carried him and his daughter along for an afternoon ride on the Devil’s Triangle.

“If you’re not very experienced, they are going to be intimidating,” he says of the tight corners. “I live in Oak Ridge, and it’s about 15 to 20 minutes away. Sometimes I come in from one end, sometimes I come in from the other if I want to follow it from Norris.”

I always make it a point to ask local riders about their favorite roads. I jot down in my notebook some of the places he mentions.

“That’s a nice ride to follow it all the way to Norris Dam and back around again. It just depends on how much time I have. I work from home, so I can pretty much take off whenever I want.”

We get back on the bikes and I follow him for a few miles, only detouring at the Route 330 turn off to answer the blinking low fuel indicator on my dash. As I complete the triangle and return to Oak Ridge, I find a room for the night and prepare for my next day’s excursion to the Secret City.

With the outbreak of World War II, the federal government purchased nearly 60,000 acres of farmland near the Clinch River in east Tennessee. The remote location offered secrecy and plenty of power from the newly completed Norris hydroelectric dam for the Manhattan Project to enrich uranium. It was here, at the Y-12 Plant, where the atomic bomb was born.

Today, Oak Ridge is no longer the Secret City. Area museums and welcome centers celebrate the town that helped end World War II with the components built here going into the Hiroshima bomb.

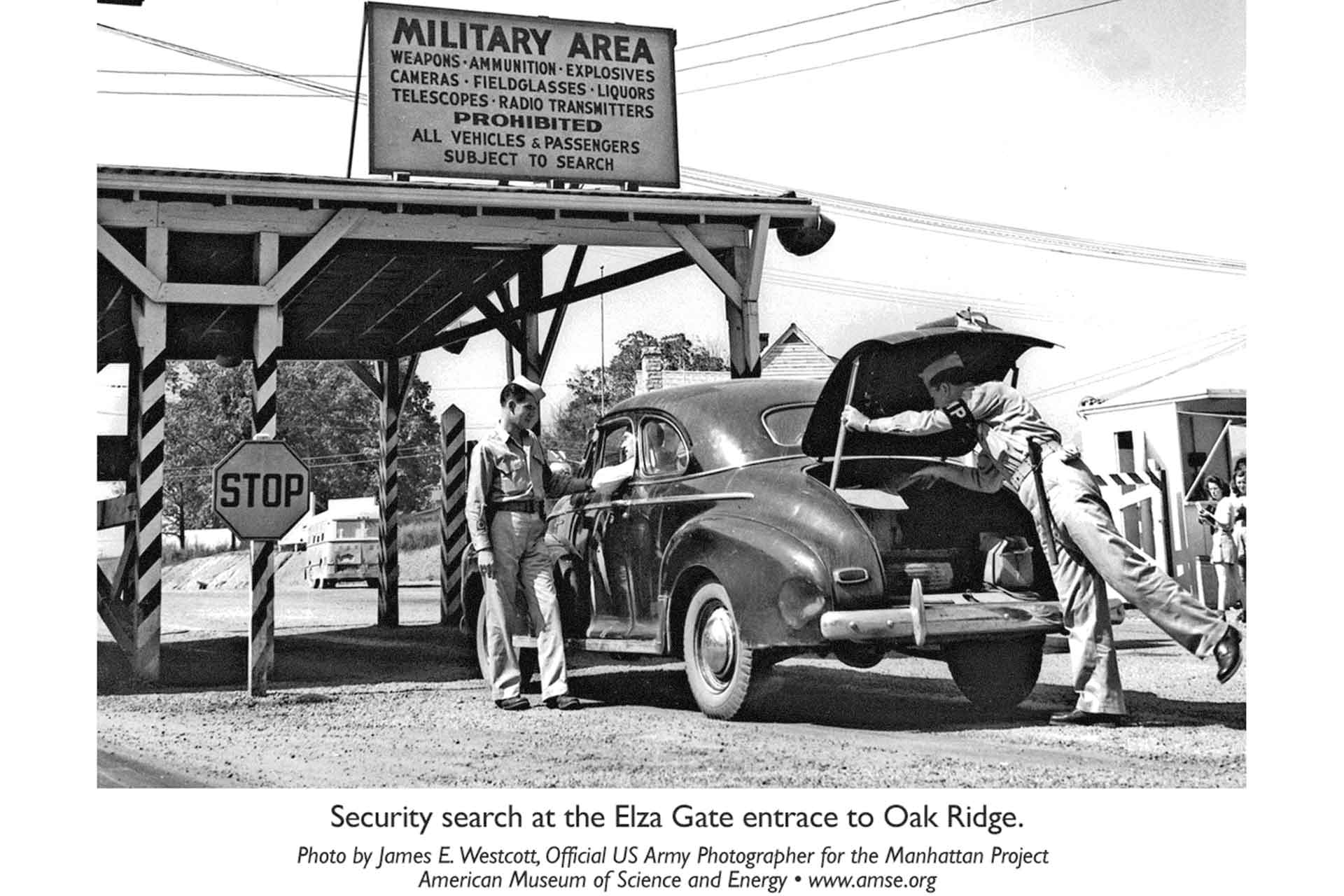

I head out in the morning toward the facility, which still produces nuclear material for powerplants, ships and even weapons. After the war, the federal government reduced its security zone around the Oak Ridge complex. In 1949, they build three “checking stations,” or guardhouses, near the entrances. They’ve been restored in recent years and placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Pulling up next to the Scarboro Road station, which once guarded the entrance to Y-12, I notice the spotlight atop the white concrete-block building. Gunports and bulletproof windows adorn the sides. Vintage furniture fills the interior. Even knowing the ominous purpose of these buildings, I still marvel at their mid-century styling and historical significance. A few hundred yards around the corner, the new gate controls access to the site. It looks like an ugly toll booth.

To my disappointment, the pandemic closed some of visitor centers and halted bus tours of the facility. I turned the bike homeward taking comfort in the knowledge that the closure merely gives me a reason to return on a future motorcycling adventure.