Pouring out of the southern Appalachian Mountains, water comes together with other water. Streams and rivers beckon to a lone motorcyclist to follow them as they spread out across the Tennessee Valley. Soon the rivers become tranquil blue expanses against the green hills, and massive gray mountains of concrete and steel lure you to throw the kickstand down and marvel at the engineering wonders from a lost age.

On a spring day in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act, part of a flurry of legislation aimed at stemming the Great Depression during his first 100 days in office. Within months, work began on the first of a series of flood control and hydroelectric dams across seven states. Norris Dam along the Clinch River would become the first completed dam, generating power for the impoverished East Tennessee counties starting in 1936.

Today, East Tennessee features nine TVA-created lakes that seem to encircle the valley around Knoxville. All of which serve as popular recreational destinations, especially for motorcyclists seeking to follow the winding lakeside roads or trace the rivers upstream to their headwaters in the mountains.

There also hides one body of water in East Tennessee formed not by engineers in the 1930s and ’40s but by the wonders of nature — The Lost Sea. Officially known as Craighead Caverns, this cave system near Sweetwater, Tennessee, features the nation’s largest underground lake not formed by a glacier.

I decided to spend a few days exploring these waterways, which is said to be the world’s fifth-largest river system.

•••

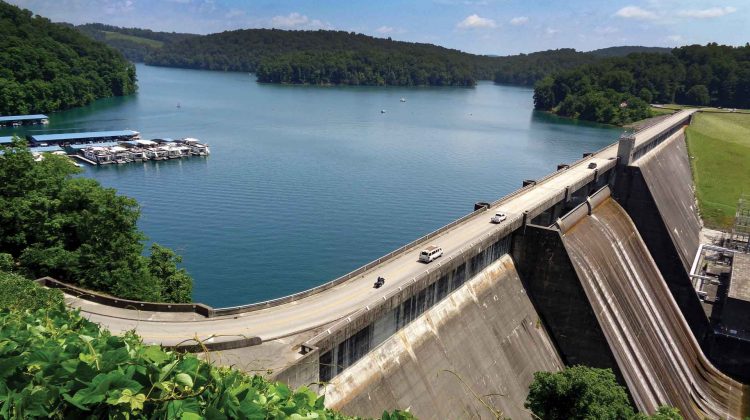

I started at the same spot the TVA chose: Norris Dam north of Knoxville. Named after the chief sponsor of the TVA Act, Sen. George Norris of Nebraska, a progressive Republican and staunch New Deal supporter, the dam stands 24 stories high and stretches more than a third-of-a-mile across the Clinch River.

Unlike most of the region’s dams, a highway runs across the top of Norris Dam. U.S. 441 begins just a few miles west and takes riders across the massive structure adorned with the word NORRIS 1936 in a stylish art-deco typeface. I note how bland today’s public works seem in comparison to the artistic details embellishing this engineering marvel. And none today seem proud to emblazon upon their edifices the motto “Built for the People.”

The road across the dam continues south, where an ambitious rider could travel to Gatlinburg, North Carolina’s Cherokee reservation, or even all the way to Miami where 441 reaches its southern terminus. Overlooks on both ends of Norris Dam make a great spot to relax and take in the 34,000-acres of dark blue waters receding for 72 miles up the Clinch River and 56 miles on the Powell.

Somewhere upstream Maddie Randolph, the fiery matriarch and mother of seven children, held off TVA officials with her shotgun on multiple occasions in the mid-’30s as the dam’s construction began.

The defiant property owner refused to take the $530 for her two-room log cabin and 14 acres along the Powell River. Her land was condemned under eminent domain in 1935, but the family remained on the land as the waters behind Norris Dam rose, salvaging their meager crops from the rising waters. The family stayed in a tent by the lake for several months until finally accepting defeat and purchasing another farm in 1936.

In total, more than 125,000 people were displaced by the TVA as it grew to include 29 hydroelectric dams and other powerplants. Looking at the all the people enjoying boating, fishing and other activities in the recreational areas created by the agency, one still feels a strange uneasiness when you realize how many poor mountain families were forced to pack everything they owned and start anew. It’s highly doubtful such a massive and controversial project would be approved today.

•••

I head northeast along the backroads closest to Norris Lake, climbing over the occasional ridgeline to follow the valley to the next of the region’s nine lakes. Eventually I reach U.S. 25E, a favorite route I’ve traveled on many an Appalachian motorcycle adventure. I know this road will take me along Clinch Mountain to one of my favorite roadside overlooks in these parts.

At the Veterans Overlook, I encounter a group of riders on cruisers stopping to admire the view of Cherokee Lake in the distance. They are all from Ohio, riding down to Tennessee on a long-distance tour of the southern Appalachians. With a roar from a pack of big V-twins, they depart leaving me to study the historic markers alone before deciding to drop down from the mountaintop for a closer view the waters below.

U.S. 25E, also known as the East Tennessee Crossing Byway, is a designated scenic highway running from North Corbin, Kentucky, south to Newport, Tennessee, where U.S. 25 — the western fork — rejoins U.S. 25 proper. I take the long sweepers downhill to turn onto Route 375, Lakeshore Drive. Here I follow the western edge of the lake, stopping at a faded sign pointing to a Civil War battlefield, submerged today by the massive reservoir. The town of Bean Station, site of the two-day skirmish in late 1863, was relocated by the TVA in the early 1940s as construction of the Cherokee Dam progressed.

Also flooded beneath the waters was the Great Indian Warpath, the major footpath used by native peoples and early settlers, including Daniel Boone.

Cherokee Dam, completed just two days before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, sits next to Route 92, holding back the 28,000-acre lake before gently releasing the Holston River to flow another 52 miles to the French Broad River and becomes the Tennessee River. One of the largest of the nine lakes, Cherokee Lake proves popular with sail boaters. It also is listed by the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society as one of the nation’s top 25 lakes for bass fishing.

•••

A short ride east on Route 92 brings me to the town of Dandridge and Douglas Lake. Here, the TVA constructed a dam on the French Broad River in record time due to the outbreak of World War II. In just one year and 17 days, the TVA constructed the 1,705-foot-long dam to provide power for two critical war efforts: aluminum production and the secret uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge 50 miles west.

Like many of the TVA lakes, a scenic marina filled with pleasure boats welcomes motorcyclists to stop to enjoy the view. Perhaps Douglas Lake’s best attribute is the stunning view of the Great Smoky Mountains filling the horizon to the southeast. Some years ago, I made a late-winter’s ride to Dandridge and marveled at the snow-and-frost covered peaks in the distance.

Douglas Lake makes a great day-riding destination for riders crossing the mountains from Hot Springs, North Carolina, on U.S. 25. I’ve often followed backroads next to the French Broad River from Asheville to Douglas Lake, marveling at how wide and blue my muddy mountain river becomes once the dam calms its nature.

•••

A few days later, I returned to East Tennessee to check out some of the southern lakes and to do a little cave exploration. Examining the map, I find the Cherohala Skyway will be a perfect route to the Lost Sea in Sweetwater.

While the Tail of the Dragon, U.S. 129, attracts more riders, the Skyway offers challenging turns, scenic views and a lot less traffic. The temperature drops noticeably as you climb above 5,000 feet in elevation on your way to the town of Tellico Plains. After a long morning’s ride across the mountains to the Tennessee Valley, I soon spot the turnoff to the Lost Sea.

As a kid in the 1970s, I would see the billboards for this cavern along Interstate 75 during family trips and beg my practical single mother to detour for this hidden wonder. She never would. It took 40-plus years, but I finally made it to this tourist attraction and happily paid the modest entry fee.

The caverns in the southern Appalachian Mountains always entice me as a riding destination, and I’ve logged many a trip that featured a stop at Mammoth Cave in Kentucky or Luray and Grand caverns in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

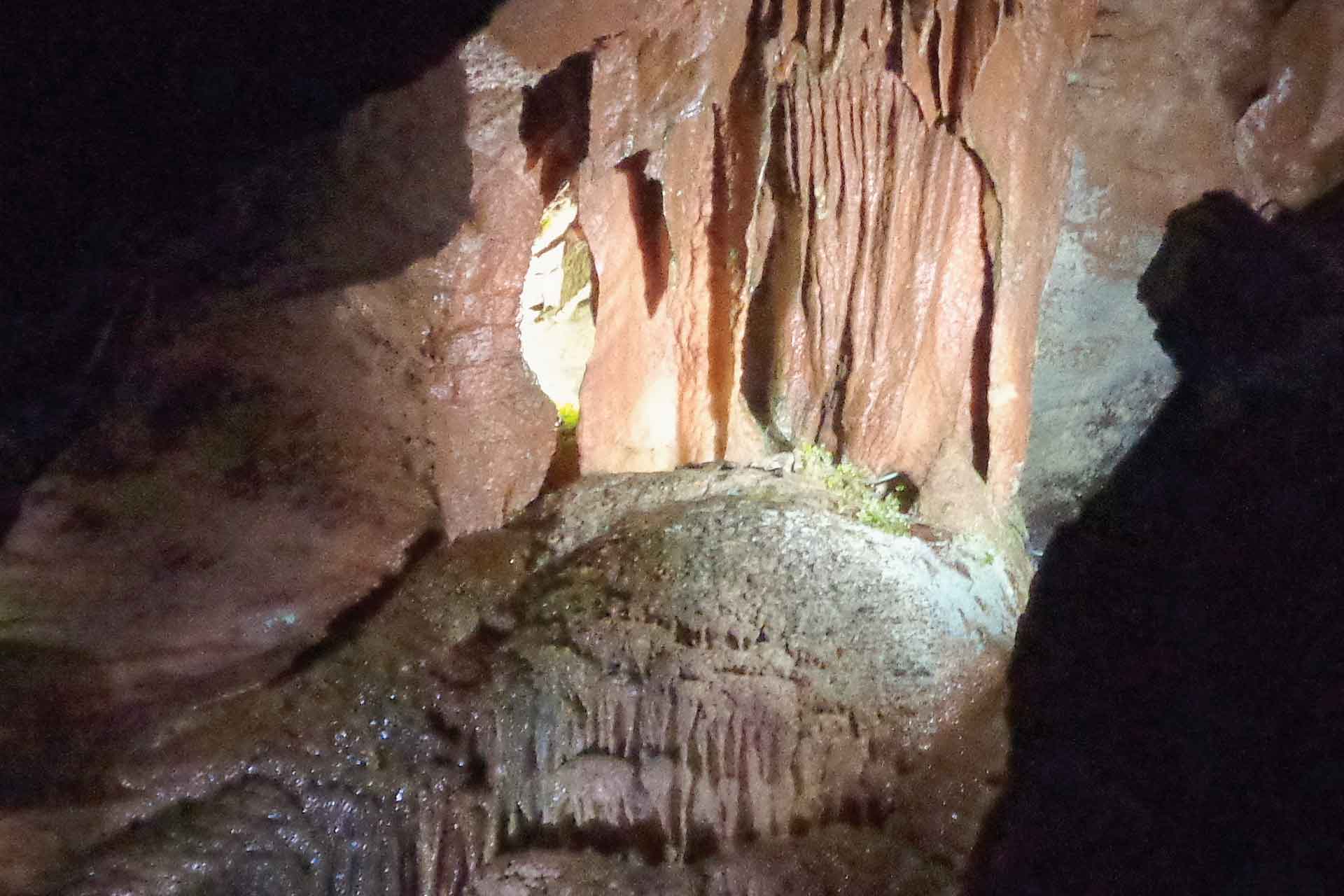

At Craighead Caverns, the official name for the Lost Sea, I wait for the tour to begin by examining the cave artifacts on display in the lobby. A reproduction of a huge Jaguar head and some paw-print castings inform visitors of the cavern’s most impressive find — the bones of an extinct big cat left here since the last Ice Age. Cherokee arrowheads and Civil War-era items also chronicle the cave system’s human occupation.

After a brief wait, the tour begins with groups descending a steel tube, installed in the 1960s, leading to the one of the cavern’s largest rooms. The friendly guides take each group along easy-to-navigate walking paths while pointing out the cave formations and historical use of the caverns. They mined saltpeter for gunpowder here during the Civil War and stashed Civil Defense supplies in here during the Cold War. All very interesting to this history nerd, but I came to see the underground lake.

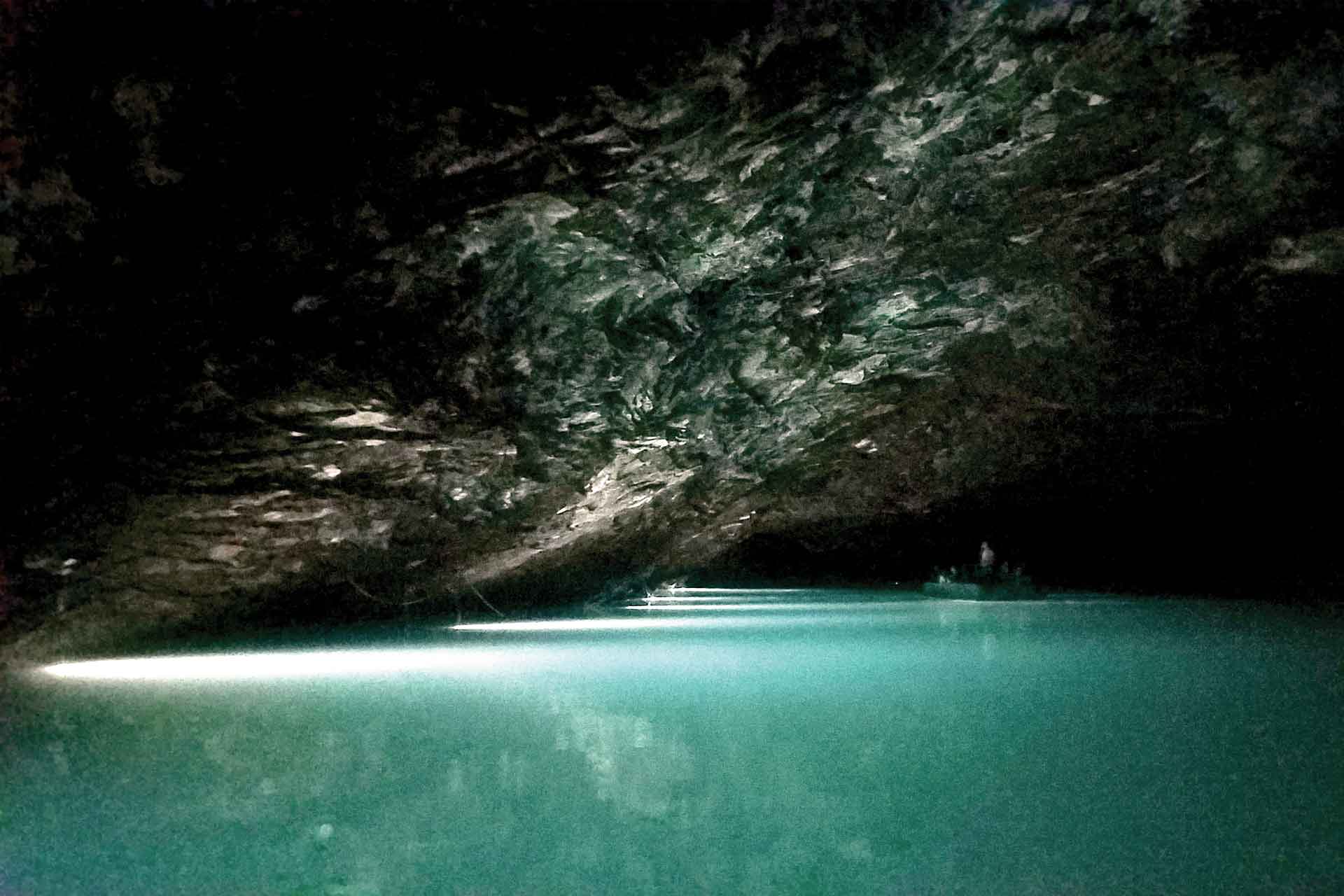

Down a steep walkway and through a narrow passage blasted out of the rock for better access, we reach a large, darkened room with docks on a turquoise pond. We board one of the tour boats, so big they had to be carried into the cave in pieces and constructed on site.

Underwater lights line the underground lake’s shore. A quiet serenity comes over visitors as they marvel at such unfamiliar surroundings. Large rainbow trout start to swarm around the boat, waiting to be fed. The fish aren’t native to the lake but stocked by the owners as another popular attraction. Guides say there are other flooded rooms connected by underwater passages, making the lake twice the size of what we see on the boat tour.

•••

Fort Loudoun and Tellico lakes, about 16 miles from the Lost Sea, feature a unique history. Each time I travel through these parts, I always pull into Fort Loudoun State Historic Park. On a peninsula jutting into the water, a recreation of the original British fort offers an immersive experience of frontier life. This fort, built in 1756 during the French and Indian War, was rebuilt in the 1930s. Upon its original construction, it was the westernmost British fort in America. Clashes with the native Cherokee resulted in the natives overrunning and destroying the fort, which returned to nature until the 20th century.

Ten miles north of the fort, the namesake dam creates Fort Loudoun Lake, a popular spot for birdwatching as it attracts herons, osprey and bald eagles. During the dam’s construction in 1942, an extension was planned to divert water via canal to increase hydroelectric power at Fort Loudoun Dam. Plans stalled until the 1960s, when the extension became the Tellico Dam project.

Tellico Dam, completed in 1979 nearly 50 years after the original idea for the reservoir, saw several delays, the most interesting of which was due to a small fish — the snail darter.

As the ’70s dawned and environmental protection made intrusive projects like the TVA dams less attractive to the public, opponents of the dam successfully sued to stop the project and protect the endangered snail darter. After much legal wrangling, Congress amended the Endangered Species Act in 1978 to exempt the snail darter from protection, allowing the dam to be completed the following year.

Westward from Tellico Lake, Route 72 leads riders to U.S. 129 and the Dragon. Before climbing out of the valley, U.S. 129 makes a leisurely cruise past the modest Chihowee Dam, allowing riders a chance to enjoy the peaceful lakeside ride before tackling the 318 turns in 11 miles as you head to North Carolina. The popular overlook on the western end of the Dragon serves as a great photo opportunity as you look down to see the top of the Calderwood Dam and its reservoir in the canyon below.

I didn’t make it to the two westernmost lakes, Watts Barr and Melton Hill, which gives me an excuse to plot them on a new route in the future.

The TVA lakes of east Tennessee were “built for the people.” Born out of the Great Depression, swiftly constructed during World War II for hydroelectric power, the assorted dams still stand today, serving their intended purpose and creating abundant recreational opportunities. Next time you find yourself wanting a new riding destination, just follow the rivers westward out the Blue Ridge Mountains. You’ll find yourself alongside a TVA lake soon enough.