If there’s any lesson in this damn pandemic it’s this: never postpone joy.

So while we can’t travel overseas and we can’t spend much time with friends and family, and when we do we have to be really careful not to get sick, we can go motorcycling.

Years ago, the International CBX Owner’s Association organized a series of rallies in Marlinton, West Virginia, and I attended several. Marlinton is not only a charming little town, but it sits at the epicenter of some of our region’s best motorcycling. So it was always a joy to attend those rallies where I met several fellow owners who have remained friends to this day.

Last week, one of them told me through social media that he was planning to return to Marlinton and would keep me posted. Would I like to go? Yes, of course! When he backed out, I looked at the weather forecast, which honestly was better than any in recent memory for an early November, and I decided what the heck, I’d go anyway.

So I contacted Andrea and Nelson, innkeepers at the Old Clark Inn in downtown and made a reservation for the following night, and then plotted the long way there on a couple of roads I’d never done. I found a way to stretch what is normally a three-hour ride from my home in Blacksburg, Virginia, into six hours.

My BMW was in the shop for an electrical glitch, so I packed the new Honda NC750X with a makeshift travel bag and stuffed it with a change of clothes and some shoes, strapped it to the passenger seat and headed out.

My home in Blacksburg is no more than 10 miles in every direction from great riding. As I headed northward toward New Castle, the sky was still overcast and chilly, but warmer with each passing mile. By the time I reached Lewisburg, I’d turned off the heated grips and opened the collar on my Olympia jacket. I decided to explore Highway 20 northward from Sam Black Church to Charmco, Quinwood, and Nettie into Richwood. Most of the leaves had lost their greenery and fallen from the trees, opening up the views and the sight distance on the highway. On nearby hillsides, sun-swathed bronze leaves shimmered. There were modest wood frame homes—in less decrepitude than in the southern West Virginia coalfields—and occasional white painted churches. The road was in good condition and traffic was scant, with passing zones on the climbs allowing me to scoot by the log-laden and tanker trucks.

Richwood is a logging town with about 2,000 souls and a tight downtown of three-story buildings and mostly empty storefronts. The town was incorporated in 1901 and at one point possessed the world’s largest clothespin factory. Who knew?

The next 30 miles on Highway 39 presented one of the most heavily wooded highways in the state, climbing Cranberry Mountain to the entrance to highway 150, West Virginia’s answer to the Blue Ridge Parkway. With its mountaintop run of 22 miles, the Highland Scenic Highway reaches an elevation of 4,545 feet and is typically one of the coldest places in the mid-Atlantic. But not on this day! Instead, I stopped at one of the many overlooks to bask in the 70-degree sunshine. Immense, crystalline views spread before me in all directions.

While I was eating a snack, a couple pulled in on a full dresser Harley. The loquacious driver said they were down from Ohio, enjoying the great weather and fantastic scenery. Stroking his braided beard, he said, “We have some good riding back home, but nothing as dramatic as these mountains.”

Leaving the Scenic Highway at its terminus on US 219, I continued northward towards Slaty Fork and climbed again, this time to Snowshoe Mountain, the mid-Atlantic’s premier ski resort. I was told that on busy winter weekends 10,000 people or more can be there, doubling Pocahontas County’s population. If there was a pandemic going on, you could never tell by the frenzied activity, with ever more lodges and condos being built, construction cranes marking the skyline.

I made a beeline to Marlinton, leaving the area’s other major attractions, the Cass Scenic Railroad and the Green Bank Observatory for another trip.

I checked in at the Old Clark Inn in downtown Marlinton where innkeepers Andrea and Nelson showed me to my room and to their covered motorcycle-only parking area.

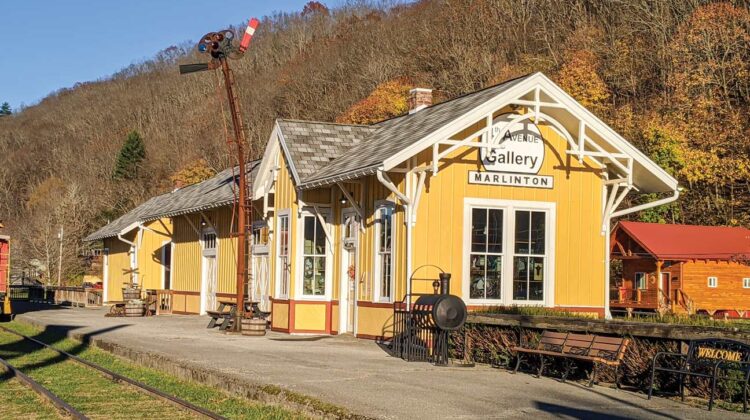

Changing my riding boots to walking shoes, I took a three-mile walk on the nearby Greenbrier River Trail, past the rebuilt train depot and a dramatic, historic water tower, until the air began to chill and the sun set behind the western skyline. The GRT stretches all the way from Cass in the north for 77 miles south to Caldwell. The dead-flat corridor hosted a spur of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway from 1900 until passenger service ended in 1959 and freight service ended in 1978.

I had dinner with old friends at the Greenbrier Grille, outside on the deck overlooking the river, lights from the far bank rippling in the water. It was surprisingly tasty—I had a shrimp alfredo—and cost $50 for the three of us, beers included.

The next morning as I was packing the bike, I had a chance to speak with innkeeper Nelson who told me how challenging the pandemic had been for his business. They had been forced to limit occupancy and to keep things scrupulously clean. But they were still seeing lots of motorcyclists and were, like so many other hospitality businesses, just trying to get through this terrible year.

My itinerary kept me on US 219, a busy road for this area, but “busy” is a relative term for the mountains of West Virginia. On this weekday morning there were only a few instances where my Honda and I were held back from our desired speeds. The road up Droop Mountain is curvy and wonderful, to the entrance of the Droop Mountain Battlefield State Park, commemorating the November 6, 1863, Civil War battle, the last major battle of the war in what had only recently become the new state of West Virginia. While the ultimate winner and loser of this battle is still debated, it had the effect of clearing most sizeable Confederate presence in West Virginia, ensuring the state’s survival.

I skirted Lewisburg and headed over to Alderson where I picked up Highway 3 eastward to Pickaway. This road is an absolute motorcyclist’s delight, curvy, scenic and uncrowded. If this road was within an hour of Asheville, it long ago would have been given some fancy and enticing name, perhaps after some body part of a mythical reptile-like monster. I was sorely tempted to turn around and ride it twice, and then a third time.

I realized on the way that I’d experienced highway hypnosis, what my Ph.D. wife calls automaticity, the altered mental state where I was able to drive safely while responding to external stimuli with no recollection of having done so. And I’d further given no thought to the turmoil of the prior week’s presidential election or the raging pandemic or much of anything else. In short, I’d found just what I went for. We must seize the day, eh, because we don’t know how many we’ll get!

I ate my snack at a church picnic area near the Great Eastern Divide north of Gap Mills and then headed over Peter’s Mountain for gas at the Paint Bank General Store. The tiny village of Paint Bank is sandwiched between two long-ridged mountains, Peters and Potts, and Highway 311 summits one and then the next, with 20 of the most exhilarating miles of mountain roads anywhere.