For us gearheads, there’s nothing but motorcycling that stirs our soul like railroads, so I decided to follow the route of the old C&O RR through the Virginia and West Virginia mountains, specifically from Crozet to Hinton.

Crozet is named after one of the more influential Virginians from the 19th century you’ve probably never heard of. Here I wanted to follow what would become the main line of the C&O Railway (later Chessie System Railroads and now CSX) westward until it reached the watershed of the Ohio River.

Claudius Crozet was technically not a Virginian at all, but a Frenchman, and not a statesman or politician like many of Virginia’s luminaries. Y’see, he was an engineer, mathematician, and educator. He built bridges, roads, railroads, and perhaps most notably, tunnels. And he provided the impetus for this motorcycle journey.

It turns out that historically, because of its topography, travel in Virginia from north to south was easier than east to west. But being ambitious people, Virginians always looked to the west in what by the middle of the Civil War would become West Virginia and beyond to the rich lands of what would become Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois and then farther.

After fighting for Napoleon, Crozet and his wife took his impressive intellect — Thomas Jefferson once called him “by far the best mathematician in America” — to the new nation of America where he rapidly made his mark, engineering the first railroad across the formidable Blue Ridge Mountains.

Crozet was described by contemporaries as irritable and intolerant of anyone who possessed lesser intellect (which was generally everybody) or had the temerity to disagree with him.

I chose what became a hot, rainless three days in July to embark on my journey.

From my home in Blacksburg, I motored my BMW R1200R on backroads to the Blue Ridge Parkway in Floyd County, then northward all the way to milepost 1 at Rockfish Gap, the gateway to Shenandoah National Park.

Readers of this magazine know all too well the delights of the Parkway for our beloved sport. But frequent reminders are in order. Past Roanoke, the elegant string of pavement climbs a knife-edge ridge with view on alternating sides, where to my left, the west, a massive sea of clouds overhung the Great Valley of Virginia, punctuated by green islands. Admittedly, Virginia’s Blue Ridge Parkway lacks the grandeur of North Carolina’s, but it is beautiful nonetheless, with sparse traffic and lots of curves. The temperature was perfect, cool at higher altitudes and warm down low, the pavement was smooth, the moon was in the seventh house, Jupiter was aligning with Mars, and peace guided the planet (or so it seemed). It was sublime!

I left the Parkway at Afton Mountain and descended into Crozet. I was eager to find something noteworthy, maybe a statue or some honorarium to its namesake, but nothing was to be found. I spoke with a clerk at a gift shop in the former train depot who told me there was an annual arts and crafts festival there, but even its promotional materials mention nothing about him. And I was getting hot.

So I retreated back toward the mountains.

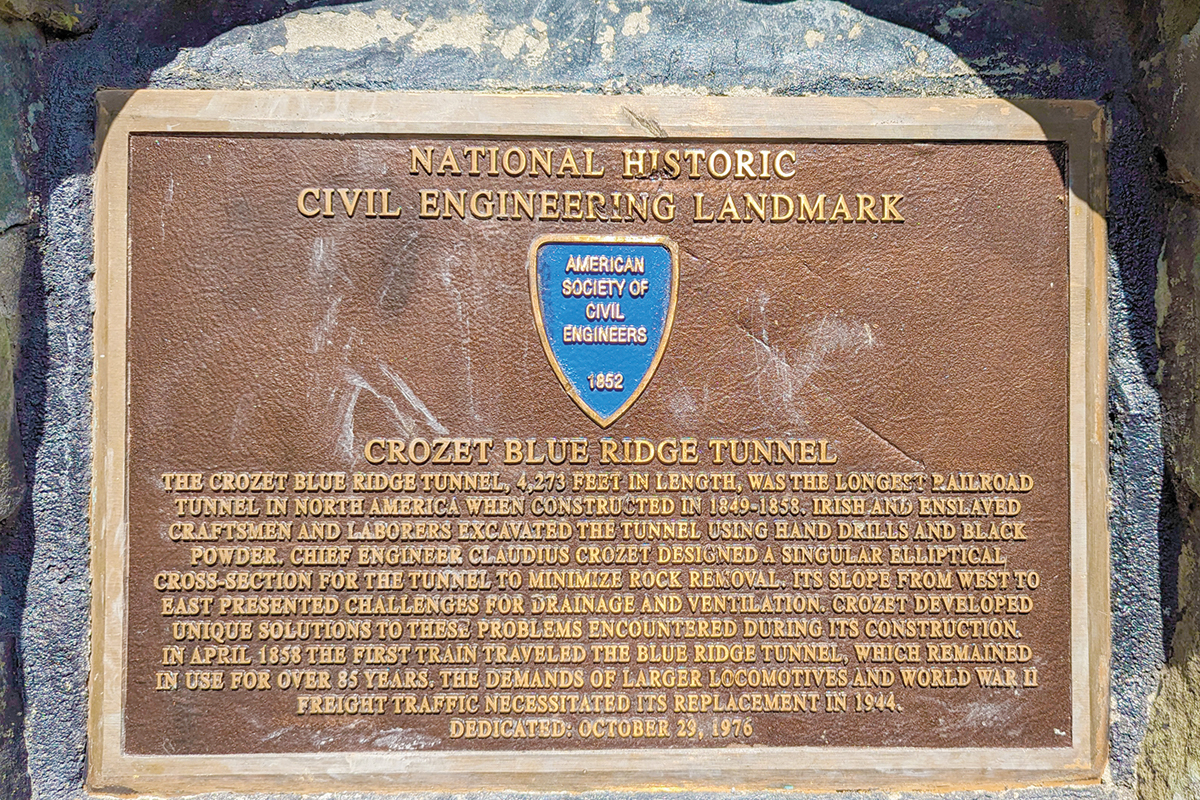

Claudius Crozet’s magnum opus was arguably the Blue Ridge Tunnel, a masterpiece of engineering for the day and now a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. The westernmost of four tunnels required to reach the Blue Ridge, it stretched 4,237 feet long, the longest in the USA at the time of its completion. Working from both sides toward the middle, using only hand drills and black powder, it was said when they met in the middle, the two teams were only 6 inches off perfect alignment. Opened in 1858, it was operational until abandoned and replaced by a new tunnel in 1944, built to accommodate larger trains. It employed 800 Irishmen and 40 slaves, with 189 recorded deaths.

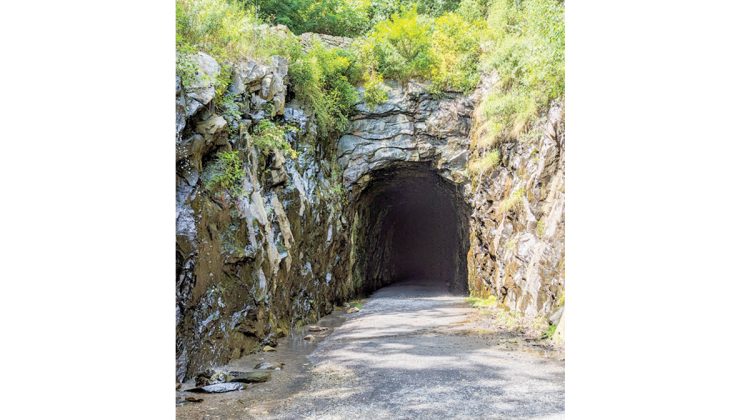

In 2020, it was reopened to visitors as a linear park. After draping my riding gear over the BMW, I walked the gravel path from a spacious parking lot 0.6 miles to the entrance, where I was blissfully greeted by a blast of cool earthen air and a shower of runoff from above. I didn’t walk far inside. It was darker than the inside of a whale in there and it gobbled up the meager light from my flashlight like it was a firefly. I’d need to come back with some serious lumen-power.

I rode over the gap and descended into Waynesboro, the next stop on the C&O, filling the Beemer’s tank with premium. I looked fruitlessly for any item of interest to report, and then kept going.

I rode over to Penmerryl Farm for the night, their sparkling pool on my mind to ease my heat frustration. Proprietors Laura and Blair had a room ready and chilled for me.

After a refreshing swim and then a picnic dinner, I spoke with Blair about what he’d learned in the three years since my last visit with them.

“I’m overwhelmed by the amount of support from guests,” he said. “There’s something special about the property that I don’t see any more because I’m immersed in it. But the reviews bring tears to my eyes. It’s just nice feedback, knowing we provide an experience that feels natural and good to people.”

Penmerryl Farm caters mostly to both motorcyclists and horse enthusiasts. There are a dozen horses on the farm.

“We like the word, ‘bucolic,’” he said. “Our guests use that word, too. I keep getting rejuvenated by people’s comments. I’m pleasantly surprised by the cleanliness of the motorcycle riders. We do lots of adventure tours and the riders and bikes get filthy. I feel a level of respect from them that they don’t trash our place. They leave it how they found it.”

The next day, I headed back to the C&O corridor in the city of Staunton. A city of 25,000 or so, Staunton has a tarnished history, although the folks at the Visitor Center won’t tell you so. It’s the birthplace of Woodrow Wilson, generally well thought of other than his overt racism, and the location of the grisly work of one Dr. Joseph DeJarnette.

While a celebrated physician and psychiatrist during the early 20th century, DeJarnette was best known for his involvement in the eugenics movement, the involuntary sterilization of folks deemed unworthy of procreation in an effort to improve the human gene pool.

In that effort, he was unwavering and unrepentant to his dying days. When Adolph Hitler established his own eugenics movement in Germany in the 1930s, he was said to have used DeJarnette’s model. By 1930, DeJarnette personally sterilized 33 women by tubal ligation, 60 men by vasectomy and 5 people by X-ray exposure. Decades later in 2001, the General Assembly denounced eugenics and expressed “profound regret” for the “incalculable human damage” the state’s eugenics program had done.

On a more positive note, Staunton has a beautiful, architecturally outstanding downtown and is economically vibrant.

I parked the BMW on a cobblestone street at the historic train station which was in disrepair. You can still board a train there, as Amtrak’s Cardinal stops for passengers from Washington to Chicago and points in between. There is no station manager. You buy tickets on-line.

I stopped in at the Visitor Center where I learned that Staunton was settled in the 1730s and the city was founded in 1747. Always a prosperous community, it was a crossroads where the original Valley Pike, now U.S. 11, crossed the C&O. At one point, it had six downtown hotels. There is only one now. People arrived from England, Scotland, Ireland and Germany. People were brought from Africa. It had and still retains manufacturing, transportation, agriculture, government, banking and entertainment. There were several opera houses. Now there is a focus on downtown preservation.

Wandering downtown, I let myself into the Blackfriars Playhouse, which houses an exquisite replica of Shakespeare’s Blackfriars Theatre. Rehearsals were going on for “Romeo and Juliet,” which I was careful not to interrupt.

Leaving Staunton on Route 254 and then to Route 42 toward Clifton Forge, I found the most bucolic (there’s that word again) riding of the journey, a mix of farmland and national forests, always with the railroad tracks nearby if often unseen beyond the dense foliage. The road was uniformly well-paved, scenic, and peaceful. My alternatively loved and hated (electrical gremlins) BMW purred along confidently and languidly.

I stopped at the small C&O Railway Heritage Center in Clifton Forge, housed in an abandoned station. Amtrak had a platform elsewhere in town. The docent seemed to have no interest in me, and I was the only guest. Maybe he sensed that I was unwilling to pay the $8 admission fee to the locomotive yard just to take a few photos of their collection.

It was too hot to drive through downtown Covington, but I stopped at the Humpback Bridge just west of town. Built in 1857, it is the oldest covered bridge in the state, one of the longest at 109 feet and has a unique humpback feature, meaning the center is 4 feet. higher than the ends. And for us RR fans, the C&O tracks are only a short distance away.

Track builders faced their next challenge as the imposing Allegheny Mountain loomed ahead. Forming the border between Virginia and West Virginia, this formidable barrier wasn’t breached until the Alleghany Tunnels and five others between Covington and the state line were built after the Civil War in the years of 1868 to 1873. I left busy, 70 mph Interstate 64 to go south on Route 159 to Crows, then back west on Route 311 to find the village of Alleghany (they spell it with an “a” around here) and the tunnel’s east portal. Where Route 311 crosses the tracks, it splits, and the westbound lane goes underneath through a corrugated metal tube and eastbound goes through a tunnel made of more elegant cut stone.

The Alleghany Tunnel goes under the Eastern Continental Divide, separating the Atlantic Ocean drainage (via the Jackson/James river system) and the Gulf of Mexico drainage (via the Greenbrier/New/Kanawha/ Ohio/Mississippi river system). The track quickly reached the Greenbrier, flowing from the north and then turning west near Caldwell, destined for the New. Caldwell is the southern terminus of what was once a spur line northward through Marlinton to Cass, but now is the Greenbrier Rail Trail.

I stopped just beyond downtown White Sulfur Springs at the entrance to the opulent Greenbrier Resort, playground of the haute bourgeoisie. The old train station is well maintained and contains a Christmas theme gift shop. But like many other stops, Amtrak only uses a landing. The Greenbrier has a lovely entrance framed by a white-brick wall and dazzling flowers, but don’t be seduced — it’s terra proibita for us commoners. I literally couldn’t find the room rates online. If you have to ask what it costs, you can’t afford it. And besides, they don’t allow motorcycles at all.

“Because it scares the horses,” I was once told (wink, wink).

I continued on to Lewisburg, which back in 2011 beat out Astoria, Oregon, as Budget Travel magazine’s Coolest Small Town. In a state where you can’t use the word “cool” alongside the name of many of its cities, indeed Lewisburg is charming and hip, while retaining its small-town character. I stayed in a single-room rented in an appealing, gadget-laden private home near the Osteopathic College.

From there, I walked into town in the hot afternoon air and wandered into the independent bookstore A New Chapter on Washington Street five minutes after the advertised closing time.

Proprietor David Craddock said he opened the store on a whim five years earlier. As I was buying a book, he told me a story, illustrative of his adopted town.

“We opened on a Saturday. Our point-of-sale system went down, and we couldn’t process credit card payments. The store was packed, and people came to the counter with stacks of books. If they didn’t have cash or a check, I said to them, ‘Take the books and come back later and pay for them.’ They all did! And they bought more when they came back. I wouldn’t expect that everywhere.”

I wandered a bit farther up the street and had a burrito at Del Sol Mexican restaurant where outdoor diners adjusted their chairs to find shady spots. A Maserati GranTurismo convertible pulled up at the curb outside, likely a spill-over from The Greenbrier’s guest list.

The next morning, I continued my westward ride, past the West Virginia State Fairground in Fairlea, and back into the “real” West Virginia of John Denver’s country roads and Merle Travis’ coal mines. Alderson is another bygone town, smack against the Greenbrier River, famous for its federal women’s prison which once hosted Billie Holiday, Tokyo Rose, Martha Stewart, and would-be Gerald Ford assassins Sara Jane Moore and Squeakie Fromme.

My favorite place is Alderson’s Store, family owned and operated since 1887 and almost a museum of yesteryear shopping. The pumpkin-colored train station still hosts passengers.

As I mentioned earlier, this former C&O line, now owned by CSX, hosts Amtrak’s Cardinal train linking Washington to Chicago. Service is terrible. There are only three trains each way weekly, on Sunday, Wednesday and Friday. I missed a train while I was in Italy a couple of years ago and had to wait 65 minutes for the next one. If you miss the Cardinal, you may wait three days.

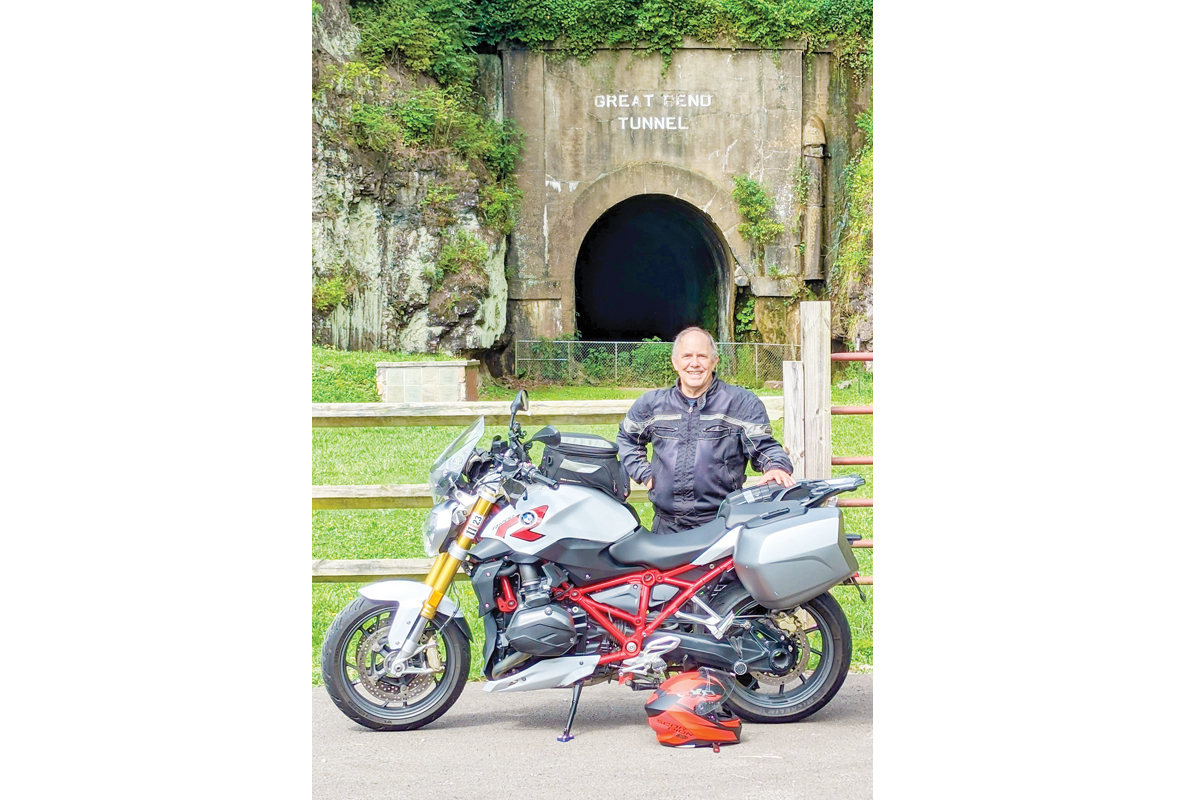

It is a short, scenic ride mostly alongside the Greenbrier River to Talcott, another village steeped in American historical lore, the legend of Ole’ John Henry, the steel-drivin’ man. As we’ve seen, railways like to avoid hills, so in this part of the world, they generally stick to the rivers. But just outside Talcott, the Greenbrier makes a mighty bend out of the way, and in the early 1870s C&O’s builders decided to tunnel under the Great Bend to save track mileage.

The C&O resident engineer was Capt. Richard Talcott, for whom the village was named. He employed nearly 1,000 workers, mostly newly freed African-Americans and Irish immigrants. Consider the technology for tunneling back in that era: robust men armed with sledgehammers would drive horizontal rods into the solid rock. The hole would be packed with Dualin, a new volatile explosive mix of nitroglycerin and sawdust (This was even before dynamite.) and then “shoot” or blast it out to loosen the rock. There was nobody, by legend, more robust than John Henry.

When a steam drill was brought to the site, the workers felt their livelihoods were threatened. Henry challenged a steam drill operator to an hour-long contest. By legend, Henry won, only then to die from exertion. Is the story apocryphal or did it really happen?

Legends take on lives of their own, but serious scholars have agreed that Henry was real, a newly freed man from either Virginia or North Carolina, and between 30 and 35 years old when he arrived at the work site in 1870. Standing six feet tall and weighing a brawny 200 pounds, he must have been a sight to behold, a Schwarzenegger of his day.

The tunnel was problematic from its opening day in 1873, with the roof lined with timbers rather than brick, leading to several fatal rock-falls. When the C&O decided to retrofit it with bricks, they placed more than 6 million in 10 years.

The tunnel was abandoned in 1931 when a new, parallel tunnel opened to handle taller trains. At the site now is a small park with a statue of the legendary figure holding a massive sledgehammer. It formed a fitting photo backdrop to my muscular, boxer-engined BMW.

The entrance is sealed off from wandering tourists by a chain-link fence, and I know of no effort being made to open it to walkers, a la the Blue Ridge Tunnel.

Then on to my last stop of the trip, Hinton. Blissfully, I found a parking spot in the shade of a four-story building on Temple Street to begin exploring. The town sits on a shelf above the plain of the New River just downstream of the mouth of the Greenbrier. Upstream on the New is the Bluestone Dam which protects the town from recurring floods that formerly plagued the railyard on the riverbank. Just downstream from Hinton is the New River Gorge National Park.

Like most of West Virginia’s coal country communities, Hinton’s heyday was decades ago, with 6,654 folks in the 1930 census to around 2,200 now. The charismatic downtown’s buildings represent the unique architecture of that era and most remain, although many are vacant and shuttered.

Hinton is the County Seat of Summers County. The courthouse is a red brick Romanesque Revival building, constructed in 1875. It has six unique 8-sided “turrets” or towers.

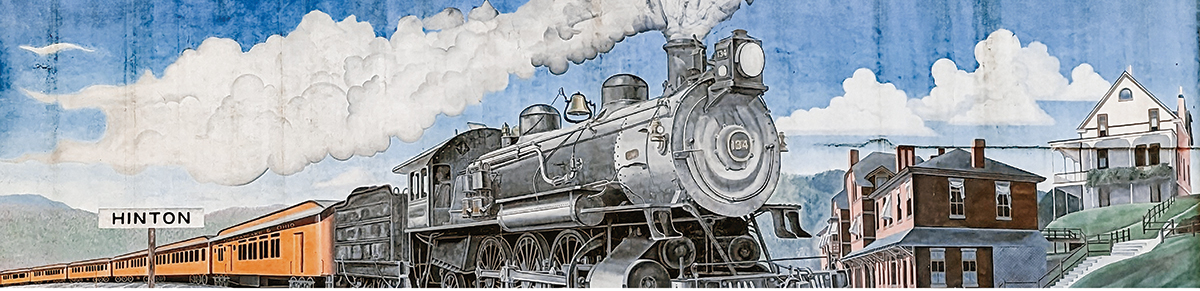

My destination, unsurprisingly, was the Hinton Railroad Museum, housed in an old department store. Its most outstanding display was maybe 100 12-inch-tall carved figures representing the historic railroad workers.

“This used to be Cox’s Department Store,” said guide Rebecca Casto. “My people are from here. I lived here only three years and graduated from high school and then left. Then, all these stores were full and bustling. The railroad was the main industry, and it was thriving. There were multiple passenger trains each day.”

The museum is filled with artifacts. There’s a model railroad upstairs that runs during the Hinton Railroad Days festival in October.

“There’s lots of recreation here with the three rivers (New, Blackstone, and Greenbrier) and Bluestone Lake. We have the New River Gorge National Park and Pipestem and Bluestone state parks,” she said. “We know the economy will never be what it once was, but it’s peaceful here. The scenery is beautiful. We’re proud of our heritage. We love our mountains. The mountains are in our blood, and they protect us. They’re in us. It’s the story of West Virginia.”

‘Nuff said!

Michael Abraham is the author of several books including “Chasing the Powhatan Arrow.” Contact him here.