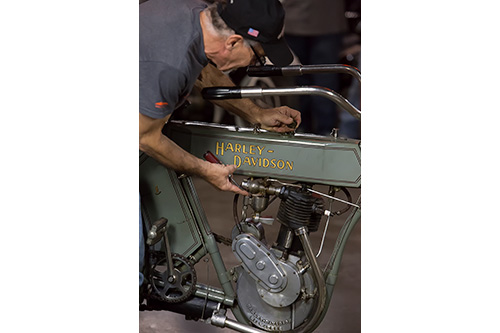

Dale Walksler bends over the 1909 Harley-Davidson and presses his mouth to the gas tank opening, then exhales forcefully to push gas from the tank into the carburetor. It’s the kiss of life, the resuscitation of a machine that hasn’t been started in decades. But knowing even a little about Walksler’s love of these old machines, it’s unclear who is giving life to whom.

On this Friday afternoon at his world-class motorcycle museum in Maggie Valley, Wheels Through Time, Walksler is filming the latest installment of “Dale’s Channel,” a subscription-based, national program in which he highlights his antique motorcycles – and often gets them up and running. “Not in a million years” did Walksler expect this rare machine to show up in his cavernous, 38,000-square-foot museum, home to several hundred rare and antique American bikes. But “a happy trade” with a West Coast friend brought the gray, single-cylinder beauty to Walksler’s business.

Before the shoot, Walksler tells a reporter he’s sick of talking about himself and his “passion for motorcycles” and he suggests the journalist watch the film crew chronicle his latest two-wheel intervention. Once the cameras are rolling and Walksler starts talking about the bike and diagnosing its problems, it doesn’t take long for that passion to surface. He has to cover the basics first – gassing it up and checking and then adding a bit of oil. These old bikes only need about two ounces. The kick-start on this bike is a set of pedals, and Walksler mounts up and gives it a few turns. It doesn’t start, and the piston seems a bit sluggish. A little brake cleaner down the motor’s gullet frees it up some.

Yes, it’s brake cleaner, or as Walksler cracks, “Anything that goes boom!”

The old Champion X sparkplug displays a spark, but the machine still won’t start, despite Walksler’s furious pedaling. “Not encouraging,” Walksler says, adding a mild epithet, as the crowd of about 40 people gathered laughs. “If I wanted patients, I would’ve been a doctor.”

Those life-giving sparks were fleeting, and Walksler determines the plug has a crack in it. He has to swap it out.

Still won’t start. Might be a timing issue, he surmises. A spring pump that moves fuel through the motor on the decompression stroke isn’t working right, and Walksler removes a small cap off the bottom of the machine and has an assistant grind a miniscule part off to free it up.

No dice. He sends it back for another fine grinding. He pedals vigorously again. Nothing.

Mind you this is live, and an audience has big expectations. They want to hear that familiar Harley roar.

The bike probably hasn’t been started since the 1950s, Walksler says, but it’s a major point of pride to him that every motorcycle at Wheels Through Times runs, and many of them are pushing a century or even more. The owner personally fires bikes up while walking the floor, much to the delight of patrons.

So the doctor has more work to do. He orders up a new spark plug wire from the assistant and puts it on. The old bike has a spark again, good fuel and oil, a working carb, a new spark plug wire, solid compression and decompression. Again, Walksler works the pedals like he’s on the Tour de France.

And this time it comes alive, the single cylinder offering up an early version of that Harley rumble. The crowd can’t help but cheer and clap. Walksler works the throttle for a few seconds, the sinews of his arms twitching as he lets the machine gobble down some 110-octane fuel. Then, like a proud papa, he wipes away a tear. “That’s a pretty emotional thing for me,” Walksler says. He talks about 1909, when the bike was built, how the four founders of Harley-Davidson built it by hand, painstakingly and with obvious devotion. They didn’t build many in ’09, yet Walksler has one – and it runs, oh so gloriously.

“You want to hear it again?” he says to the crowd, getting the obvious answer, then mounting the pedals. “I can’t stand it.” He fires it up again, basking in that sound. This model had a “town and country” feature on it that allows the rider to work a control arm that dampens the muffler sound for city riding, Walksler explains, smiling and looking at peace.

Why talk about your passion for motorcycles for the millionth time when you demonstrate it every week at your shop?

Walksler notes that he’s spent 700 straight Sundays at the museum he built up from scouring barns, garages, personal collections and defunct dealerships for rare models, which include a 1909 Pierce once owned by Steve McQueen, one of Evel Knievel’s red, white and blue jump bikes, and a mysterious 1916 Traub, in mint condition and found stored behind a wall in a Chicago residence in 1967.

Walksler rebuilt his first Harley as a teenager, and he was a goner. He was a Harley dealer for years, picking up some rare bikes along the way, as well as some fantastic vintage cars also on display at Wheels Through Time, which brings 135,000 visitors annually to this small town in the Great Smokies. One of those visitors, Christy Elliott-Gonzalez of Louisville, Kentucky, hits the nail on the head – both in describing Walksler’s efforts to get the 1909 running, and in unwittingly describing the man’s life-long devotion to bikes. “Perseverance,” she says. “It gives an example of how you can only get what you want if you keep on trying.”

She and her husband, José , brought their two kids, Soleila, 13, and Samuel, 6, to the museum, even though José says he stopped riding a few years back. Like the people who flock to Wheels Through Time from all over the country and even oversees, José Gonzalez says he’d heard so many times how awesome the museum is he had to put it on his bucket list.

Walksler, 64, takes obvious pride in the place, which displays machines from various time periods, as well as military bikes, racing machines, hill-climbers and more. But he really is tired of talking about himself, and today he insists the attention should go to the team he’s built over the years. One of those team members, the mechanic’s assistant/videographer during the “Dale’s Channel” shoot, Kris Estep, came to Wheels Through Time in the spring. At 33, he’s always been an antiques hound and motorcycle lover, and as a resident of nearby Bethel has always been a fan of the museum.

“There’s so much to see here, you can’t see it all in one visit,” he said, adding that he wanted to work for Walksler to soak up some of his encyclopedic knowledge of American motorcycles. “The amount of knowledge he has, not only mechanically, but historically, about all types of engines and bikes, it’s just an amazing thing. I think he’s the best there is at this.” That would in part explain Walksler’s success not only with Dale’s Channel but other television shows, including, “What’s in the Barn?” which also ran nationally. He’s also been featured on “American Pickers,” “American Restoration” and “Chasing Classic Cars.” After a half century in the game, he is a certified motorcycle guru.

Andy Norris, a Brit who came to America in 2012, in part to experience Wheels Through Time, has a knowledge of bikes that almost rivals Walksler’s. But he still marvels at Walksler’s encyclopedic knowledge, as well as his acumen for finding and collecting bikes. “Dale is part blood hound, part historian, part all-round detective, but he’s a 100 percent authentic, and a really nice man,” Norris said.

Walksler started his collection in 1969 in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, moving it to Mt. Vernon, Illinois in 1977, where it was housed at the Harley-Davidson dealership Walksler founded. In 2002, he made the move to Maggie Valley, a motorcycling mecca close to the Blue Ridge Parkway and other gorgeous, curvy mountain roads. He restores about a dozen bikes a year, and Wheels Through Time raffles off a vintage bike off every year. Walksler works on the bikes himself, often with tools that are as old as the bikes.

Before the show, he notes that the 1909 Harley was “singularly built, with the eight hands of the four founding fathers of Harley Davidson.” It was a “fork in the road” bike for Harley, as that year the company was shifting from a flat belt drive to a v-belt. “During this transition, there was a lack of building time in 1909, so they had to spend an enormous amount of time building this bike,” Walksler says. Nearby are more vintage Harleys, and Walksler just can’t help but slip into tour guide mode, sharing that encyclopedic knowledge.

“This area is ’12-20, all Harleys, the best collection of ’12-20 in the world,” he says. “This is a 1920, all original, fully accessorized – the best ’20 in the world. This is a 1919 with smooth, shiny paint, built with a factory racing motor, one of a kind, only one known.” He pauses at a 1916 Harley with a sidecar – with the controls in the sidecar, which has room for two. A wealthy lady had it built for her and her son, he says. He can’t stop.

“That’s a ’12, that’s a ’15. This is a ’13,” he says. “These are all special models that you’ll never see another one. There’s actually maybe four of these known. This is the only 1913 known; that one went back to the Harley factory in 1914 for an upgrade.” He’s got another of McQueen’s bikes, this one with messenger pigeon carrier on the back, “the only one like it in the world.”

Wheels Through Time has about 300 bikes, so of course there are more stories. He’s got the personal motorcycle of Oscar Hedstrom, co-founder of Indian Motorcycles and, as Walksler says, “the man who invented the motorcycle.” A 1916 Flescher Flyer is literally the only one in the world, and it’s not far from the only known Elk motorcycle, built in 1912-13, and that’s within walking distance of a Thor motorcycle that was built and owned by a guy named William Ottaway. Who’s he, you ask? “He was so damn smart that in 1913 Harley-Davidson hired William Ottaway, and he is the man responsible for making Harleys go,” Walksler says. “This is Ottaway’s personal Thor, one of a kind. Every part on that bike is built uniquely to itself.”

He’s also got the personal bike of Will Henderson, the man given credit for revolutionizing the four-cylinder motorcycle in America. Walksler has been collecting for half a century, and people often approach him now with rare finds. While he might tire of talking about himself, he never tires when it comes to talking bikes. He pauses and enjoys a moment of silence, the smell of motor oil and steel and rubber wafting by.

“I have more blessings than anyone in the world,” he says. “There’s no collection like this in the world.”