I took my Honda NC750X on one of my favorite routes from my home in Blacksburg, Virginia, sampling the roads, valleys and mountains that make my area such a motorcycling mecca. Westward from the dramatic Narrows of the New River, I rode the sweeping turns of scenic Route 61 to Rocky Gap and then Tazewell, northern terminus of the section of Route 16 now known as the Back of the Dragon. From there, I went north on 16, crossing an invisible line not on any highway map away from the limestone mountains of Virginia’s ridge and valley region and into the sandstone, coal-bearing mountains of southern West Virginia.

A dozen miles north of Tazewell near Bishop, Virginia, everything changed except the enveloping greenery on the hillsides flanking the road. Coal conveyers arched over the highway. Massive industrial coal processing operations appeared. Towns got smaller and increasingly more decrepit. Many homes, stores, and schools lay abandoned, some burned-out shells. Store buildings were boarded-up.

From our motorcycling perspective, 16 south from Tazewell gets all the marketing, but there are many sections north into McDowell County, West Virginia, and beyond, that are equally challenging. I stopped for a picnic lunch at a nice public park with picnic shelters and playground equipment in War, the only city with that name in the country. Nobody else was there.

Onward I continued through Yukon, Bradshaw, Iaeger, Hanover, and Gilbert, all showing signs of advanced decay and diminishing populations. From our perspective, that’s a benefit, in that there are few vehicles on the road. On weekdays, there are coal trucks to deal with, but on this hot Sunday, I had these roads mostly to myself.

At the summit of a pass at Horsepen Mountain on U.S. 52, once a major highway stretching from the balmy beaches of South Carolina all the way to the North Dakota border with Canada, I turned onto one of the strangest roads around, a 9-mile stretch of the King Coal Highway. This project, envisioned as a four-lane superhighway 20 years ago to stretch 95 miles from Bluefield to Williamson, has been largely stalled, completed in only short segments, including this one near Red Jacket. Its roadbed was left behind by a mountaintop removal operation, a cooperative venture between the coal mining company and the state as a use for the reclaimed corridor. In practice, now it is a mere two-lane road with no more lanes necessary because it’s largely vacant. After spending the last hour riding mostly in the narrow hollows, it was refreshing, and several degrees cooler riding near the top of the mountain. And it’s fast; pick any speed you want, your exuberance governed only by the road’s maddening dips and rises.

Notable up there were the Mingo Central High School, built a decade earlier to consolidate and replace four schools throughout the county, all which were losing student population, and an airport that I never saw and can’t imagine anybody ever uses. On a more positive note, it was grandly scenic up there, with views rivaling the Highland Scenic Highway on the other side of the state.

I descended steeply under huge overhanging cliffs into the Tug Fork Valley and found my lodging, the Historic Matewan Bed and Breakfast on Main Street, a one-way loop through the historic downtown. The inn was a charming place, with a large central living room and dining area, filled with historic photos and knickknacks. I was directed to the Coal Room, an interesting coincidence as I’m currently working on a book about coal and coal mining. It had a spacious bed with a beautiful quilt and in the bathroom a claw-foot tub and wrap-around cloth shower curtain. Old wooden floors creaked under my footsteps.

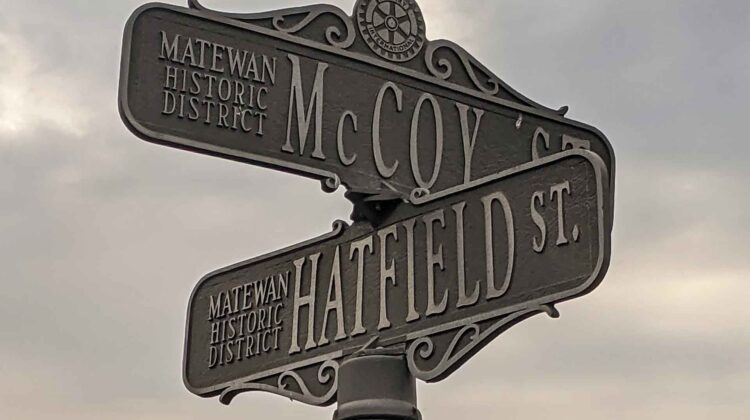

Rivulets of human blood ran down the streets of notorious Matewan, West Virginia, on May 19, 1920, and into the tempestuous Tug Fork River after a gun battle that left 10 dead and dozens more wounded. It is a quintessential American tragedy, subject of books, plays, and movies, filled with horror, intrigue, and romance, and was hugely consequential in American labor history. But infamous Matewan’s tragic reputation long preceded that fateful day, indeed even before it became Matewan and was merely a deeply remote wilderness hard against the Kentucky/West Virginia border in the central Appalachian hills, as epicenter of the decades-long Hatfield and McCoy feud, perhaps the world’s best-known familial clash.

I washed my face and swapped my riding gear for walking shoes in preparation to meet my friend Paul Phillips. Paul and I met a few years earlier while working on my last book, “Chasing the Powhatan Arrow,” a travelogue from Norfolk to Cincinnati following the rail line that ran literally behind the B&B. Paul and his friend James Baldwin, a recent resident of Matewan who moved there because he became fascinated by the massacre story, took me on tour of the town while James regaled me with his version of it.

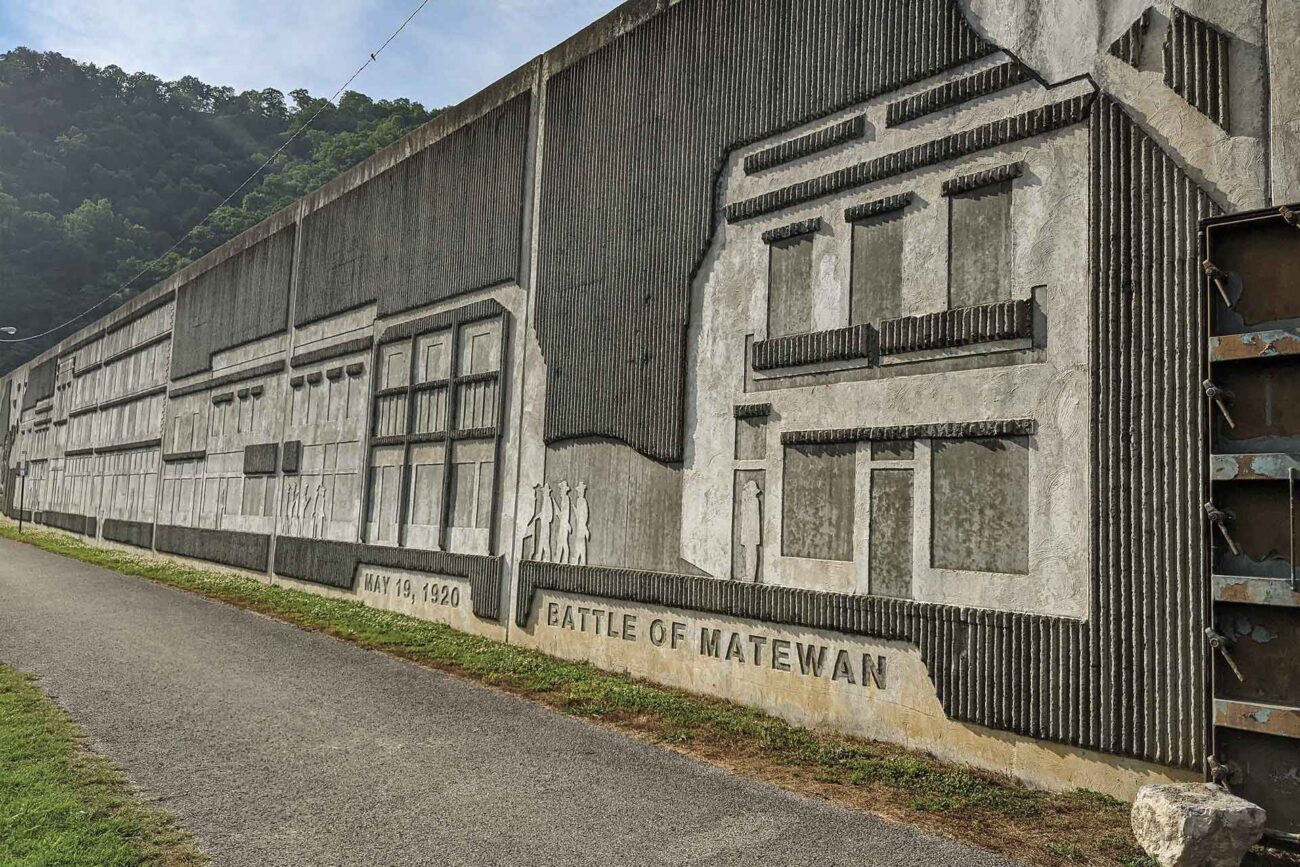

Matewan itself is situated on a floodplain above the Tug, which has had the nasty habit of overwhelming the town every few decades. After the particularly devastating flood of 1977, the Army Corps of Engineers decided the best way to prevent further destruction was to build a concrete wall separating the town from the river. There are several reinforced metal doors, for pedestrians, cars, and railroads, and some are massive, intended to be slammed shut when storm warnings arose, sealing in the town. I’m told they’ve been closed four times since the wall’s completion in 1997, but so far, floodwaters never have made it up the significant embankment to even reach the bottom of the wall. I also was told the wall cost more than the assessed value of the town it protects.

During our walking tour, James told me his grandfather, William G. Baldwin, founded the Baldwin Detective Agency in 1890 which later became the Baldwin-Felts Agency. Its agents were sent to Matewan that ominous 1920 day to evict coal miners from coal company homes, leading to the shooting and death of many of miners and agents. James Baldwin told me that after becoming infatuated by the massacre, he moved from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Matewan, where he lives and breathes it every day. He leads tourists along the footsteps of the Baldwin-Felts agents to the point where many of them met their fateful end.

Baldwin explained, “It began in April 1920 when six members of the Stone Mountain Coal Company joined the union. It was in their contract with the coal company that they’d not join or even talk about the union. Many miners were recent European immigrants who were recruited from Ellis Island. They were in debt by the time they arrived in West Virginia. The coal companies really owned them. Many were already coal miners in Europe, but they didn’t realize they were entering slave labor. They were charged for the trip from New York, charged for the equipment they needed, and charged for their house. They were paid in script rather than cash, and could only make purchases in the company store. Conditions in the mines were primitive and dangerous.

“There were no union mines here then. When they were evicted, they ended up in tent colonies, forced to eventually leave the area to work in union mines. Local law enforcement officials were sympathetic to the miners and refused to do the evictions. So the coal companies hired the agency to force the evictions. They sent 12 men.”

Long story short, the day ended in tragedy with seven of those men, including two of three Felts brothers, dead along with two miners and the mayor, Cabell Testerman. It is estimated that in the melee, more than 1,000 bullets were fired.

The town’s police chief, Sid Hatfield, who was also sympathetic to the miners, survived the day. Twelve days later, he married Testerman’s widow, Jessie Lee Maynard. In retaliation for the massacre, the surviving Felts brother ordered Hatfield executed — assassination style — a year later on the courthouse steps of neighboring McDowell County, along with Hatfield’s companion, Ed Chambers. Hatfield’s new wife, Jessie, and Chambers’ wife — who tried to defend him — watched in horror. None of the attackers were ever convicted of Hatfield’s assassination, claiming “self-defense,” although neither Hatfield nor Chambers were armed.

Incidentally, Ms. Maynard outlived a third and fourth husband as well. Jessie Lee Maynard Testerman Hatfield Pettry Jennings died in 1980 at age 86. Somebody needs to write a book about her. Matewan is not for the meek. But I digress.

We continued our walking tour, crossing the railroad tracks to the outskirts of town, past the lovely sandstone M.E. South Episcopal Church where the town’s children were hid away during the massacre. We went to the prospective terminus of the Mate Creek Rail Trail that Paul is working to have developed above an abandoned rail line.

We walked the outside of the perimeter wall, artfully cast with raised-relief scenes of Matewan’s history, including the Hatfield-McCoy feud, whose epicenter was Matewan even before the town was incorporated. The river, seemingly innocuous and incapable of ever rising above its high embankments to destroy the town, was lovely and clear. Fishermen sat on its banks and waded its shallows. It was picture-postcard pastoral and peaceful, belying its tortured past.

That evening, Paul, James and I ate at one of Matewan’s two restaurants. Paul said, “I had barbeque last night, so let’s do Mexican.” Between the server’s Spanish accent and COVID mask, we barely understood anything he said.

Paul left Matewan for college in 1969 and returned in 2017. He said, “It’s much quieter now, but healthier. There were endless coal trucks rumbling through town then. Now tourism is building. You see lots of 4-by-4s on the streets. The air is cleaner, as is the river. We had two banks that both closed recently. I figured it was the death knell for the town. There’s more activity now, but still little commerce.”

A train rumbled by interrupting our conversation, pulled by three black Norfolk Southern locomotives. The horn was deafening, but the squeal of steel wheels on the curving steel rails was as loud and more grating.

I slept well in the comfortable bed, other than being occasionally awoken by passing trains and their infernal horns. The trains literally shook my bed, like one of those 25-cent bed vibrators, only this was free.

In the morning, the owner of the Historic Matewan House Bed and Breakfast, David Hatfield, joined me for breakfast (Did I mention that seemingly half the town is still surnamed Hatfield or McCoy?). He was born and raised in Matewan, retiring as a locomotive engineer. He came back to town to “try to keep things moving.” He’s been involved in several other ventures as well, including the annual marathon and half-marathon run.

The building was initially a private residence but has lived several lives.

“We’re in our seventh year at the inn,” he told me. “We need more guests. Our clientele is people visiting family, people enjoying the (off-road) trails, or enjoying the history. Fishing. Kayaking. People just passing through. You are at the center of an eight-mile radius of 99 percent of the Hatfield and McCoy feud activity.

“We’ve been left behind economically now that coal has diminished. Our area has yielded billions in coal revenues, but the expenditures have gone elsewhere. Right now, we’re still isolated. Our county (Mingo) is still diminishing in population. We’re forced into a tourism economy because there is nothing left. The Hatfield-McCoy Trail is our life-support. I don’t want to sound bitter. We’re independent people. We need more visitors to see what we have. Our B&B is still below the national average in occupancy.

“We don’t need 30,000 visitors per weekend like Gatlinburg or Pigeon Forge. We need a fraction of that to be thriving. How do we get there? We’re perfect for motorcycling, with curves and scenery. Our people are our best asset. We may be known as Bloody Mingo, but our people will treat you like you’re family. It’s an intangible, not on the map; you have to come to experience it. But all our visitors feel it.”

I walked across the street to visit the West Virginia Coal Mine Wars Museum where I was met by the lovely Kim McCoy (What did I tell you?), its docent. She told me, “My maiden name is Hatfield; my ex-husband is a McCoy. That’s a story itself. We’re descendents of the feuding families.

“The great thing about Matewan, we will always have our history. We are a gem of history. There are Hatfield and McCoy Feud sites. We have the Matewan massacre that occurred here in town.

“What happened here just over 100 years ago resonated throughout our country and around the world. We are still seeing the effects today in ongoing labor struggles.

“This museum is solely about mine wars. We have artifacts from around 1890 until the 1930s. We have oral histories. We reopened at the end of April from COVID and we’re already busy. We’re doing around 100 guests a weekend. We moved here in the fall of 2018 from a smaller space across the street and everybody is enjoying the new space.

“The visitors are the best part of my job here. I share my family history and I hear theirs. I’m learning as I go.

“I’m a West Virginia girl. That means strength, resiliency, resourcefulness. You have to be of a certain nature to live here in these mountains. I still grow a garden. I know what greens grow in these mountains and when to pick them. My grandma taught me things that are irreplaceable. None of my city cousins know these things.

“I’ll never be anything but a mountain girl. Ever. I’ll never leave West Virginia. If the shit hits the fan, we know how to take care of ourselves around here.”