Prepare to have your sensibilities slashed, pummeled, and eviscerated by the reality of contemporary McDowell County, West Virginia.

Your Appalachian Mountains have quaint villages, picturesque farms, forests, country inns, wineries, orchards, and breweries. Your upscale towns and cities have bistros, brewpubs, delicatessens, vegan cafes, and chocolatiers. You’ll leave all that behind when you reach McDowell.

McDowell County is real, raw, hardscrabble Appalachia. It is a cultural maelstrom, a visceral vortex of broken dreams, fractured bodies, and ruined landscapes, a woven texture of human triumph but overwhelming tragedy. One of America’s poorest places, its story is of Appalachian coal mining, and not a single paragraph of McDowell’s wrenching and fascinating history can be written without the word coal.

From the days the first shovelfuls were loaded onto railroad cars in the 1880s until this moment, McDowell’s destiny was inexorably linked with the black rock that burns. Hitting a peak of almost 100,000 souls in the 1950 census — when it was West Virginia’s third most populous county — today it hosts around 17,500, shrinking daily. It is an impoverished ghost of its former self. Its residents suffer the lowest life expectancy in the nation, with high levels of obesity, smoking, and drug dependency.

McDowell is a terrible beauty, a land ravaged with almost post-apocalyptic scars.

So with that introduction, why would you go there? To broaden your worldview. To understand the aftermath of non-renewable resource extraction. And to partake of its fabulous roads! I have made more trips there than I can count, and I am drawn to McDowell like a moth to a burning flame, knowing I may get my wings scorched, but drawn nevertheless.

On this trip, I rode my new Honda NC750X into McDowell on SR 16 at West Virginia’s southernmost tip, north of Tazewell, Virginia. Somewhere near the state line, I crossed an invisible boundary between the limestone mountains to the south and the coal-bearing sandstone rocks of southern West Virginia. And everything changed.

There’s a palpable sense of descending as one enters McDowell (pronounced “MAC-dal” by the locals), as if its entirety, or at least the portions where people live, is within the crevices of a confining, deeply corrugated landscape. I can’t remember ever seeing an outdoor photograph of anything in McDowell — a home, church, tipple, or train — that didn’t have a wall of forested mountainsides behind it.

Neither words nor photos, neither qualitative nor quantitative analyses, can adequately describe the reality that is contemporary McDowell. Through the tiny communities of Squire, Newhall, Cucumber, and War, the scenes of economic destruction were everywhere. Abandoned houses. Abandoned stores. Abandoned tipples, churches, and schools, many with deep vegetation enveloping and reclaiming them.

There was the house that was burned-out by fire, clearly many years earlier, still a standing shell with a blackened satellite dish still attached to a charred rafter. There was the wood frame house with the collapsed roof, a good-sized tree growing from within. There was the church with the boarded-up door, broken windows, and the collapsed steeple. Occupied wooden clapboard houses were close to the street, with tiny yards sporting trampolines and swing sets surrounded by chain-link fences.

Everywhere was the detritus of a former industrial era, rusting and abandoned. Bulldozers. Trucks. Cranes. Mining machines. Bales of coal mine conveyer equipment. There was a vast, suspension bridged conveyer overhead, chunks long missing and presumably pulled to the ground by everlasting gravity. Convenience stores had more pickup trucks and ATVs (which are legal on public roads) than cars. One of the few bright spots on an otherwise moribund economy, riders bring their ATVs from neighboring states to enjoy a vast network of trails using former mine access roads.

And an intense fecundity! Hillsides were clad with deep, pervasive greens of grape vines, Virginia creeper, honeysuckle, and especially invasive, voracious kudzu.

I took SR 83 westward to Bradshaw, where just to the south was the village of Jolo, famous for the area’s most widely known serpent-handling church. I didn’t stop.

Signs of overt, devout religiosity were everywhere. In Bradshaw’s pocket park across the street from the City Hall was a white painted sign with black lettering of the Ten Commandments. Churches outnumbered stores, with names like “Mile Branch Church of Living God” and “Twin Branch Pentecostal,” many sporting signs extolling the faithful to attend services and to pray. I’m certain every church in the county is facing diminishing membership as parishioners die and move away; nobody is moving into McDowell County. A McDowellian friend once told me, “Even our non-religious people are religious.”

Beyond Bradshaw is the impressive new River View High School, one of two in the county, opened in 2010, a welcome sign of modernity. No doubt, with virtually no job opportunities in the county, most of the 100 or so annual graduates are destined to either join the military — West Virginia has the highest per capita military participation in the nation — or find one of the few coal mining jobs left. For decades, McDowell’s biggest export next to coal is people, especially the young and talented, to better jobs and opportunities elsewhere.

I continued northwards to Iaeger on SR 80, the Mountaineer Highway. Founded 100 years ago, Iaeger’s fortunes reached a zenith in 1950 with a population peaking at nearly 1,600. Now fewer than 400 remain. Its downtown is on a spur from the main highway, US 52 (the “Main Line” to the locals), and not one in 10 buildings is still occupied.

I parked the Honda in the shade of an abandoned building and walked the deserted downtown. Pigeons flew in and out of the broken windows of the 3-story former First National Bank building that had clearly not been operational for decades. A long train pulled by five black Norfolk Southern locomotives rumbled through with dozens of double-stacked container cars screeching steel wheels against the steel rails.

I peered into a storefront window into what looked to be a former newspaper front office. It looked like the neutron bomb had hit, because other than chunks of acoustic ceiling tile crashed to the floor, nothing appeared to have moved an inch since former employees last locked the door and walked away. Dated computers sat on the desks and a paste-up table had a sheet of paper with the words “Subscribe today,” on it.

My psychic compass turned eastward towards the county seat of Welch. On the way, just past the location of famed railroad photographer O. Winston Link’s immortal photo of a grand locomotive steaming past a drive-in theater where he superimposed a jet airplane on the screen, I took the road less traveled through the micro-villages of Roderfield, Davy, and Capels.

This road, County Road 7, followed the Tug Fork River’s most perilous canyon (where 50 miles downstream, it separated the warring Hatfield and McCoy clans), slithering parallel to the straighter Norfolk Southern rails, both above the rushing Tug. In an endless series of switchbacks and S curves, this road demanded my full attention and skill. Still more poverty, more decrepitude. As recently as 2015, two-thirds of McDowell’s households still straight-piped their sewage to the creek.

This is not Disneyland, folks.

Throughout the county, roads followed the river bottoms and were consistently curvy. I doubt there is three continuous straight miles of highway anywhere in McDowell.

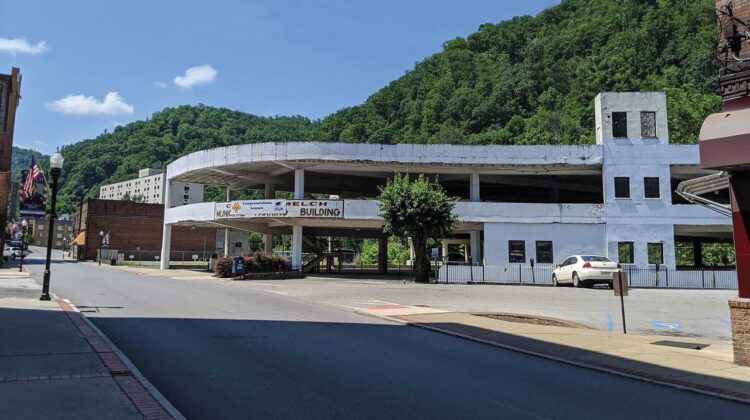

The once bustling Welch is the county’s government center and most populous place. Along Welch’s Wyoming and McDowell Streets were buildings of beautiful stone and brick, built when architecture meant something. Most were vacant; one large picture window displayed three wooden crosses. Anecdotal stories speak of frenetic shops, stores and restaurants from its heyday in the 1930s through 1950s, but every census since has shown fewer people. So crowded and geographically confined was Welch that its municipal government built and operated the nation’s first multi-story parking building in 1941. It still stands today, fully vacant.

Parking my bike in the shade of a nearby tree on the hot day, I snacked at the amphitheater-like riverside park, where local muralist Tom Acosta’s artwork adorned the entire side of a 5-story building. The place was eerily quiet, with nobody else in the park, nobody on the nearby sidewalks, and few cars passing by.

I trudged up the hill to the magnificent 1893 Romanesque Revival style courthouse where back in 1920 Sheriff “Smilin’” Sid Hatfield of nearby Matewan and a friend were gunned down execution style as their wives stood by watching in horror. Nobody was ever arrested for the double-murder. There’s a state historic marker alongside the steps telling Sid’s story, but mysteriously never mentioning that Sid took his last breath there or even the reason for the sign’s placement. Maybe they’re ashamed.

Welch’s only restaurant of any renown is the historic Sterling Drive In, with its checkerboard linoleum floor, Formica tabletops, and large awning over the parking area. Everything else was a franchise chain.

Before continuing home, I took a detour to the south to Coalwood, the village made famous by writer Homer Hickam in his autobiography Rocket Boys (later made into the movie “October Sky”) about his upbringing in a coal town destined for depletion. Only a few buildings remained from his era, all abandoned, including the general store, bunkhouse and machine shop where most of its dozens of windows were shattered into shards of broken glass. The only tourist amenities were a row of interpretive signs detailing Hickam’s Coalwood.

Heading back to Welch, my mind reeled with the tragedy of coal mining. The entire multi-county region was pock-marked with “strip jobs,” or mountaintop removal mines, arguably the most destructive industrial operation in history, where literally thousands of square miles of the region’s mountains were destroyed to reach and exploit thin seams of coal. Coal mining made this area’s mineral rights owners rich and everybody else poor for 140 years. Now everybody is poor. It’s the resource curse: McDowell has given America’s factories and power plants more coal than any county in the Eastern United States and is now among its poorest. And yet for decades, coal fueled the American industrial juggernaut and warmed millions of homes.

I left Welch and headed home on two-lane US 52 south through a continuous string of decrepit and decaying communities, like tarnished beads on a moldering rosary. Superior. Kimball. Vivian. Keystone. Northfork. Elkhorn.

I thought about all the people I’d met from McDowell, those who moved away and those who still lived there. Many expressed a weighty sense of nostalgia, the profound loss of geographical mooring that we humans cherish and the emotional distress that they could never go home, as indeed the home they once knew was forever gone, swept into the maw of poverty and decay.

Most of the folks I’d met on my prior explorations were nice enough. Although they were reserved, provincial and insular; all were patriotic, proud of their coal heritage and of their great, largely misunderstood state of West Virginia. Many were curious about my curiosity; why did I come? The answer largely was beyond my ability to articulate.

In Switchback, I stopped to photograph a stupendous railroad bridge sweeping above the road. A black man emerged from a modest house and greeted me, saying that I was welcome there as long as I liked. “People come from all over the country to photograph the bridge,” he said. “We’ve had people come from California.” I realized he was the first person with whom I’d spoken since my arrival in McDowell.