A few days earlier, a buxom, wet and nasty bitch named Helene came our way up from Florida, uninvited and unwelcomed, and for many people in many places throughout our divine mid-Atlantic mountains, life would never be the same.

The hurricane absolutely devastated several communities, large and small, mostly in North Carolina and Tennessee, but also in far southwest Virginia. The North Carolina stretch of the famous Blue Ridge Parkway won’t be ready for our motorcycles for maybe as long a year.

But other places were more fortunate, and in some cases a few miles made a big difference. I thought I’d check out some areas that might take up some of the slack in the next riding season. With a heavy heart, I headed toward the Bluefields, sister communities on the Virginia/West Virginia border.

Turns out that Bluefield is the only city on the 400-mile border. How that came about is a great story. Stand by.

Leaving my home in Blacksburg, Virginia, on the gleaming red and white BMW R1200R, I headed west to Fairlawn and crossed over the New River, still brown and swollen from floodwaters, but blissfully back within its banks. From there, I went through Dublin, over Cloyd’s Mountain (scene of an intense — although small — Civil War battle on May 9, 1864), then Mechanicsburg, Hollybrook and Rocky Gap. Near Rocky Gap, I encountered a couple of work crews chain-sawing storm blowdown. Then I ascended East River Mountain, which hosts the state line.

With its north/south trajectory in Virginia, Interstate 77 boasts two major tunnels, one under Big Walker Mountain and the other under East River Mountain. Please don’t use them, because the venerable U.S. 52 that goes over both mountains is infinitely preferable, being wonderfully curvy and scenic.

Atop East River Mountain is a nice viewpoint, once home to one of West Virginia’s most prominent welcome centers. In October 1960, residents funded and opened it to travelers to Bluefield, dubbed “Nature’s Air Conditioned City,” offering West Virginia-made projects such as coal sculptures, glassware and arts. The coming of the interstate robbed it of sufficient traffic and it eventually closed. But it still offers sweeping, expansive views into Southern West Virginia.

Because of its lofty elevation of 2,611, Bluefield experiences unusually cool summers with the temperature rarely reaching 90 degrees. So as a promotion, back in 1939 the Bluefield Chamber of Commerce began offering free lemonade to anyone stopping by once the temperature reached 90. It’s a tradition that lives on today. I’m told the temperature is checked at the official National Weather Service thermometer at the nearby Mercer County Airport — if you ask me it should be in a large, digital display at the Chamber’s front window. In any event, for the record, the most recent heat wave was July 17, 2024, the first free lemonade since 2019.

I took my first break and snapped photos of my boisterous BMW R1200R, a bike seemingly made for these curvy roads.

The road plunges off the mountain and quickly spills into the city of Bluefield, the largest city in the Mountain State’s southern coalfields region. Bluefield has a fascinating, industrial history.

As far back as Thomas Jefferson’s 1782 “Notes on the State of Virginia,” known reserves of coal lay underground in multiple layers in the western part of the state, northwest from the Blue Ridge barrier. But prior to the Civil War, there was neither a market for vast quantities nor any way to carry coal to domestic and international customers. Local settlers simply used small quantities of coal to heat their rustic homes. That all changed with the coming of the railroads and the industrial boom of the late 19th century.

Built in the 1850s, the Virginia and Tennessee rail line originated at Lynchburg, crossed a low point in the Blue Ridge near present-day Roanoke, and then traversed the Great Valley of Virginia southwestward to Bristol. After the Civil War in 1882, Philadelphia industrialists formed the Norfolk and Western Railway, incorporating the V&T and several smaller lines. Almost immediately, they set their sights on the rich coal fields of southwest Virginia and southern West Virginia. The coal rush was on.

Coal and railroads had a tight, co-dependent relationship: you couldn’t power a locomotive of the era without coal, and you couldn’t move coal — especially in these tight, mountainous areas — without a railroad. When the railroad was extended into a hollow, it was because coal was there, and mining commenced immediately. With our nation’s insatiable thirst for the rock that burns, thousands of people including newly freed Blacks from the Deep South and immigrants from poor regions of Eastern Europe flooded into the area. McDowell County, west of Bluefield and West Virginia’s southernmost, swelled to nearly 100,000 people in 1950.

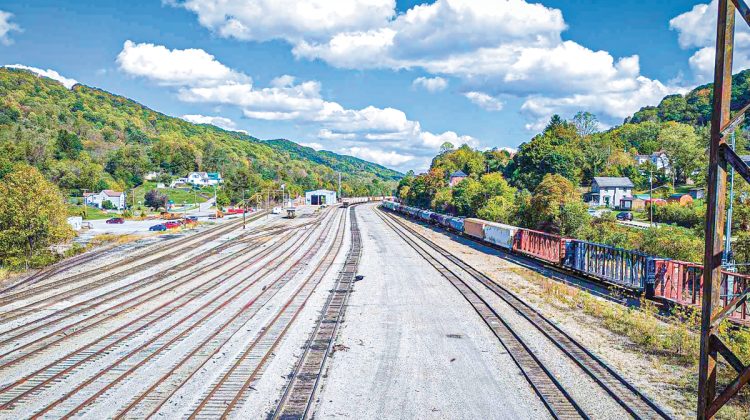

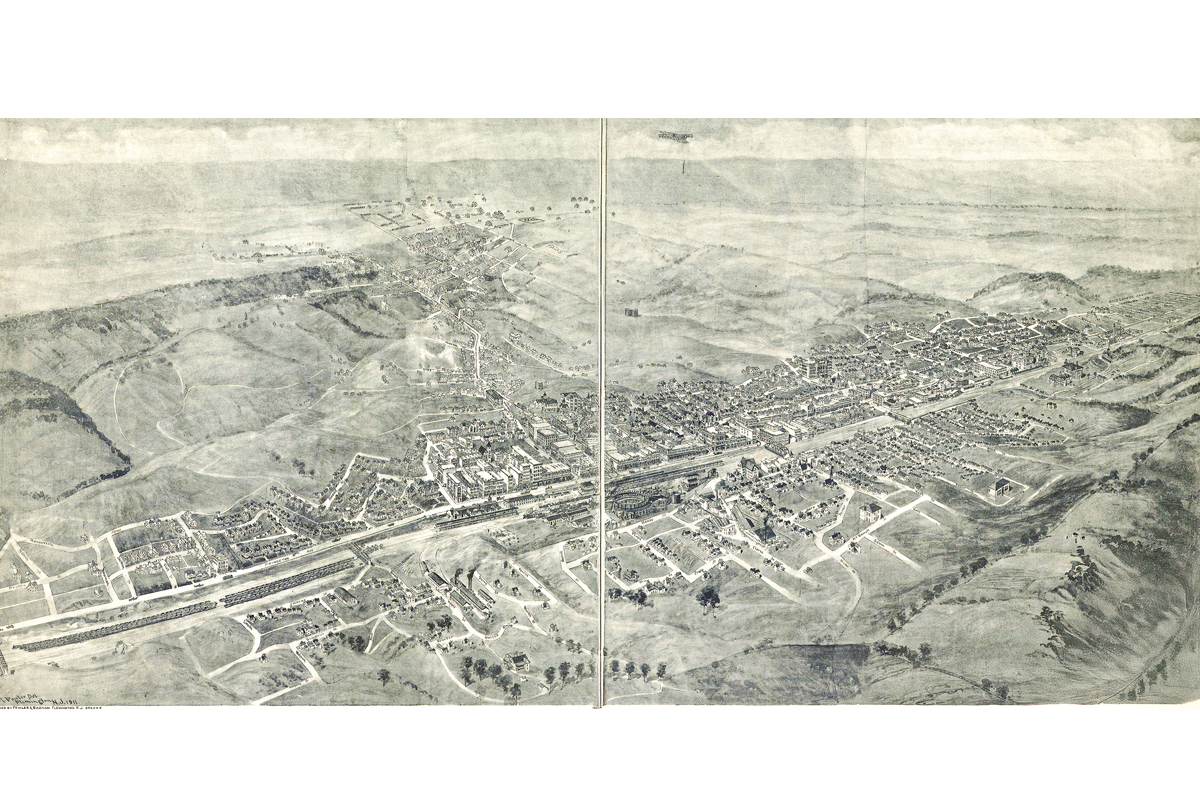

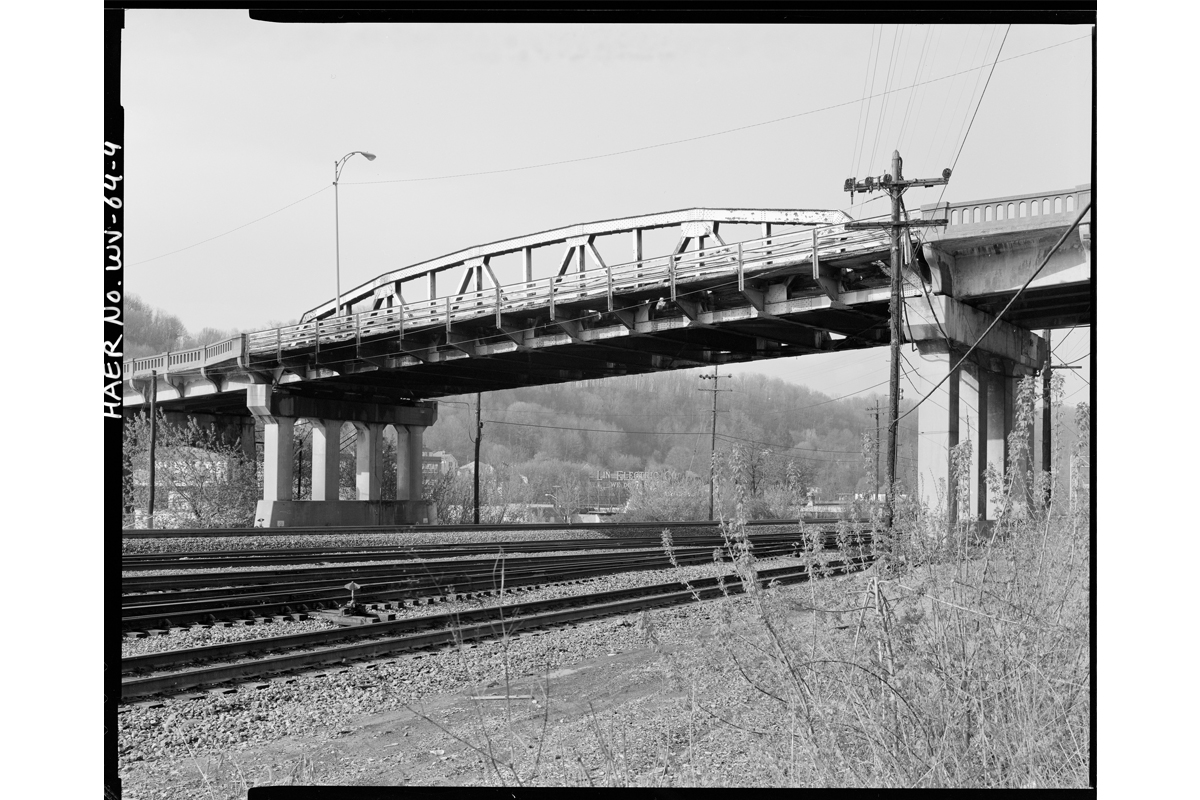

N&W surveyors sought a place to aggregate railroad operations, a place that had an east-west orientation and a slight “hump” for gravity-fed switching of cars allowing feeder trains from throughout the coal fields to build longer trains to make the 350-mile journey to the port at Norfolk. They found the perfect valley just inside the West Virginia line at the northern base of East River Mountain and quickly laid a series of tracks. They named their new city Bluefield, after the blue blossomed fields of chicory.

Being a mono-economic community, Bluefield’s fortune mirrored that of the coal and railroad industries, meaning after its explosive growth in the early 1900s, its population has diminished since. Swelling from a mere 1,775 people in the 1890 census, Bluefield peaked in 1950 at 21,500 and was an economic powerhouse, a regional hub for railroad operations. Shops, stores, clinics, banks and law offices flourished. It has declined to an estimated population of 9,400 now. Cities with diminishing population face a series of financial challenges. But on a positive note, it’s never hard to find a parking space!

I’m not a Harley guy, but flowing into the city on Bland Street, I was sucked inside Cole Harley-Davidson where I found a delightfully warm welcome. Bedecked in HD’s trademarked black and orange, ebullient Michele Marin greeted me and offered glowing insights to her adopted Mountain State home. Relocating from northern Virginia a few years ago, she found motorcycling paradise.

“My (Northern Virginia) friends and I came down to Bluefield often,” she said. “This was our favorite destination. Every road in this area is an incredible motorcycling road. It’s not one. It’s not two. I’d been coming down for years and I’ve lived here now for two-and-a-half, and I’ve still not done them all. Bluefield is one of the best-kept secrets for motorcycle riding. The best thing is the traffic, or rather the lack of it. You’re not competing. There’s seldom anyone in front of you. The backroads are incredible but even the major highways are beautiful.”

I told her Southwest Virginia and southern West Virginia have far fewer people than Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee. Here, there’s seldom anyone in front of you. When I crossed the mountain on U.S. 52, the one car I encountered pulled over and waved me around.

“You’ve got the Back of the Dragon 30 miles from here in Tazewell,” Marin said. “You’ve got all of Virginia’s valley roads. To the northwest of here, you’ve got the coal region and the hollows. Northeast you’ve got the New River Gorge National Park and farther the Highland Scenic Highway and the Monongahela Forest. Bluefield is a gem.”

The junction of Virginia and West Virginia here is geologically fascinating and complex. Virginia’s topography is characterized by long limestone mountains. On the West Virginia side are jumbled, “craniated” coal-bearing sandstone mountains that from space resemble the surface of a brain.

“Literally the roads brought me here, but the hospitality has surprised me, especially the biker scene,” she said. “During this disaster, liberal or conservative, black or white, biker or anybody, people were just looking to help.”

Bluefield has an impressive skyline, crowned by the former 1920 West Virginian Hotel at 12 stories and now an office and apartment building.

“Bluefield is not as busy as it once was, but people haven’t given up. They’re refurbishing downtown and putting in a new park. It’s a beautiful little town,” Marin said.

When riders come in from other places, they’re happy to be here, she said. They can’t wait to get to the roads. We educate them about places to go.

“I started working here as soon as I arrived. Business is good. This is a destination. Harley wants to branch out to all enthusiasts. When we have rides or events, everyone is welcome. We promote a lifestyle, the experience about being on the bike, any bike,”

Beth Moore, Cole Harley-Davidson’s general manager, is a Bluefield native who returned after 35 years.

“I’m overwhelmed by the number of people who come from all over the country to ride here. Coal is only one of our natural resources. The beauty is our greatest natural resource,” Moore said. “One of our customers comes annually from Michigan. His friends give him a rough time for always going to West Virginia. I think a lot of people don’t even realize West Virginia is a separate state. His friends probably couldn’t think of any attractions to bring him here. We’ve been portrayed poorly, but it’s beautiful here and the attractions are endless. Great riding. Great people.”

Harley is about a lifestyle, she said. The dealership deals with people’s passion, and there’s usually a smile on their face.

“I talk with people moving here from Texas and California,” she said. “It’s about a sense of personal freedom. Mountaineers are always free. Homes and land are affordable. I always feel at home in the mountains; they’re like an embrace.

Departing the dealership, I pulled up at 1405 Whitethorn St. to pay homage to Bluefield’s most famous son, John Forbes Nash Jr. One of America’s most famous and prestigious mathematicians, Nash made fundamental contributions to game theory, differential geometry and partial differential equations. Hampered much of his life with mental illness, he was nonetheless prolific and influential. Indeed, he possessed “A Beautiful Mind,” and his life was portrayed in the 2001 movie of that name. There was no sign of any recognition for him on that quiet residential street.

I’ve never been able to locate the home of Bluefield’s other famous native son, musician Maceo Pinkard, who in 1925 wrote the iconic “Sweet Georgia Brown,” about an irresistible Black prostitute. It’s been the theme song for the Harlem Globetrotters since 1952. No surprise we usually hear it as an instrumental.

I rode through downtown, which was quiet and clean, with several surprisingly tall buildings. Because the population of the city has halved, there was considerable excess infrastructure. In 2023, a process began to demolish eight buildings in the downtown area, including the old JC Penney and eight-story Montgomery Ward. I’m sure the decision was unpopular with some people — nobody wants to see a whole city block leveled — but what can you do with an eight-story building without tenants and no prospects for future tenants.

At the intersection where Bland Street splits, with northbound to the right and southbound to the left, is the Chamber of Commerce of the Two Virginias. Above the building is the iconic cursive “Chamber of Commerce” and in front, a multi-faced decorative street clock on a pole.

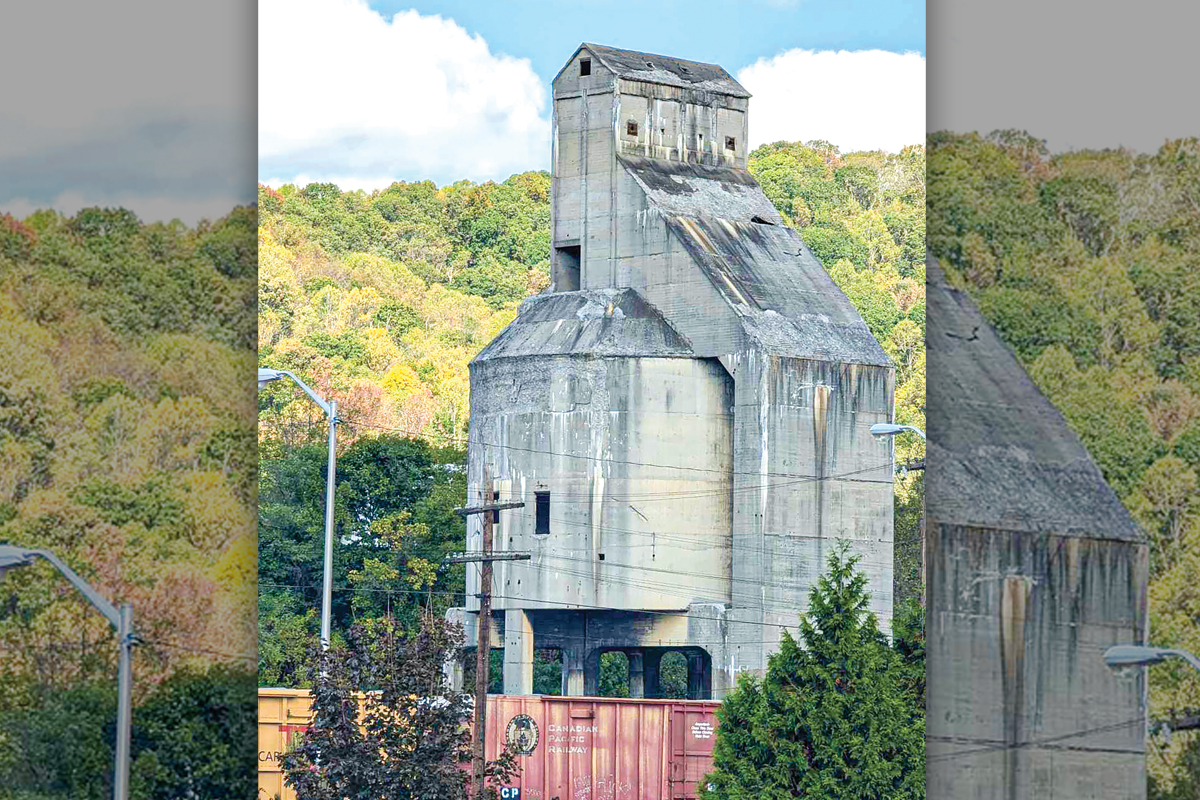

At the bottom of the hill, Bland Street meets Bluefield Avenue, paralleling the rail yard, Bluefield’s reason for existence. There is an iconic coaling tower lording over multiple tracks and rusting inventory.

Leaving Bluefield and heading west, I ironically re-entered Virginia and the town of the same name on that side of the border (Yes, Bluefield, Virginia is west of Bluefield, West Virginia.). Situated on the same valley, Bluefield, Virginia, actually has a longer history. The town developed around a small post office named Pin Hook in the 1860, and then was known as Harman after a Civil War hero. Finally, the town was chartered as Graham in 1884, named for Thomas Graham, one of those aforementioned Philadelphia capitalists. It became Bluefield only in 1924. Its population zenith was 5,924 in 1980 and has been mostly stable since.

•••

During the early years of the 20th Century, Bluefield, West Virginia, was growing at a much faster rate than Graham, Virginia. A referendum was held in Graham to consider changing the name, a vote of 287 in favor and 223 against. At a park at the state line on July 12, 1924, a mock marriage ceremony was held to celebrate the renaming, attended by the governors of both states. To this day, it is the largest gathering ever held in the region and the only time in the 20th Century when both governors were in Bluefield together. To accentuate the celebration, Wingo Yost of Graham tied the knot with Emma Smith of Bluefield. Speaking her vows, Smith was married with one foot on either side of the state line. The governor of Virginia was the best man and the governor of West Virginia gave away the bride. The moment she officially became Mrs. Wingo Yost, the results of the election were certified and they cut the ribbon. Mr. Yost and Miss Smith became husband and wife and Graham became Bluefield, Virginia.

Even now, Bluefield, Virginia’s high school is called Graham High School and the teams are the G-men. Each year, the G-men face off on the Mitchell Stadium gridiron against the Bluefield Beavers in an intense rivalry. The stadium is currently home to both schools and the G-Men are the only high school team in the nation whose home stadium is in another state.

•••

I stopped in Bluefield, Virginia’s compact downtown to shoot some photos, including one of the old Graham National Bank. Time constraints and my diet prevented me from checking out the Roasted Bean and Evan’s Sweets, the latter the home of what I’m told is the Bluefields’ best ice cream.

Heading home, I stayed on the superhighway, U.S. 460 that links the Bluefields to my home in Blacksburg. As Michele suggested, even the major roads are beautiful, snaking past forested mountain ridges and along the New River. From the road, I could see some riverside campgrounds where trailers had been displaced, smashed against each other by the force of the floodwaters. Fortunately, recovery here will be rapid.

While my heart breaks for those in the North Carolina and Tennessee mountains who have lost everything, and while many roads will be closed indefinitely, for those seeking a motorcycling destination in 2025 the region around the Bluefields presents a great option.

Michael Abraham is the author of “Keepers of the Tradition” and seven other books, available at bikemike.squarespace.com.