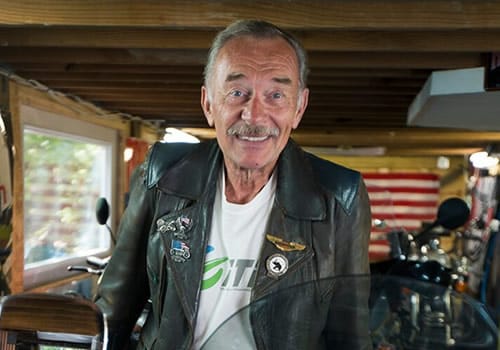

Sitting in his office chair – a race car seat on swivel wheels, naturally – Roland Linder draws a visitor’s attention to a black and white picture of a much younger version of himself involuntarily dismounted from a speeding motorcycle.

“Did too many of those,” he says with a wry smile. “Crashed three times that day. Not my day. We did finish, though.”

But ask him how many crashes he had over a 10-year motorcycle racing career, the 66-year-old native of Belgium answers with a dab of racing philosophy rather than a number.

“In order to be fast on a motorcycle, you need to go past an edge,” Linder said. “If you don’t pass that edge, you never know how fast you are. Then you have to back down. It takes time to figure that out.”

A world traveler who raced motorcycles in Europe before moving to the United States in 1980 to race GT and GTP cars (LeMans-type cars) and run a driving school, Linder settled down just outside Columbus in Polk County 10 years ago, accompanied by his wife of 48 years, Helene.

Linder last raced cars professionally in 2012, his team coming in second place in the 24 Hours of Virginia endurance race.

“I got very tired, and I realized I’m not 25 anymore,” Linder said. “So I decided to stop racing entirely.”

He did not slow down, however. Linder remains much in demand as a driving coach, working at times for big companies such as Mercedes Benz and Ferrari, but he also runs his own driving school. The clients are usually the uber-wealthy who can afford a Ferrari Enzo or Ford GT but don’t really know how to drive it – “Double clutch, matching RPMs, that sort of thing,” Linder explains.

It does not always go smoothly.

In 2006, a client driving his own $1.6-million Ferrari Enzo in a road race in Canada got a little squirrely in a turn, gave the monstrously powerful car too much gas and ended up in the ocean. The driver and Linder, coaching from the right seat, were unhurt, although the owner’s pride suffered.

In 2002, Linder got his shoulder torn out of the socket when another client struck a wall.

Clearly, this is not a career for the risk-averse.

“The wall moved in front of me,” Linder said with a chuckle. “Again, the client was driving.”

While Linder, a bit stooped but still remarkably fit for his age, freely admits to myriad motorcycle mishaps, he prides himself on being a safe, albeit incurably lead-footed high-performance car driver, whether it’s a Vintage Jaguar or a McLaren super car capable of hitting 200 mph.

“I’ve never wrecked a car, never gotten a ticket,” Linder said. “You see, I drove Indy cars, the most exotic vintage cars. It’s amazing the diversity of the cars I had the chance to drive.”

He’s also had a long-running love affair with motorcycles, growing up racing friends on a scooter for the equivalent of five bucks. His first real motorcycles were gleaming American monsters, Harley-Davidsons. At different points he owned Harleys from 1943, ’53, ‘75, and ’79.

Linder grew up in an orphanage, running away at one point and working at a gas station in his late teens. At 18, he secured his professional motorcycling racing license and began a successful 10-year odyssey on European road races.

Back then, they’d simply close the roads in a town and race.

“Miss a turn and you’re in the butcher shop – that’s why they called it ‘Butcher’s turn,’” Linder said. “Miss a turn and you’re in the chapel – chapel turn. Safety was nil.”

From 1968 to 1975, Linder worked as a mechanic for Le Mans racing teams, his Porsche-sponsored team winning the GT class twice.

As he talks, his cell phone rings – not a normal ringtone but rather the sound of a Ferrari screaming through the gears at breakneck speed.

Linder also enjoyed success in the United States, living in Colorado and competing and placing in the money in endurance road races and other events, including rallies in Texas, Virginia, Nevada and his home state.

Over the years, he made most of his money from sponsors, as “a hired gun” driving for the big companies when needed, and running his driving school.

While his affection for his first love, motorcycles, never waned, Linder’s body did. In the early 1990s, he sold his collection of street bikes.

“My back was killing me so bad, I couldn’t ride motorcycles,” Linder said. “I concentrated on (cars) until two years ago. I just couldn’t sit on the bike.”

A few minutes later, the screaming Ferrari ring-tone goes off again, and this time it’s Linder’s surgeon. They discuss Linder’s arm and shoulder pain and agree it’s time for another surgery, partly because his right arm has been killing him, partly because he wants to keep riding.

Yes, motorcycles. Of course he got back into riding. Three years ago a friend and former teammate – Linder points to a guy in a yellow Porsche on his wall of pictures – gave Linder his Harley Road King.

The Belgian also got a nudge from Dr. Laura Ellis, an Asheville resident who took up motorcycle racing nearly five years ago and now owns her own team. Linder says she “talked him into riding again,” letting him get out on a track by himself.

Ellis took Linder to a dirt bike track in Tryon and let him ride her KTM two-stroke 250.

“He blamed me on that day for him getting back into motorcycles,” Ellis said with a laugh.

She suspects Linder wouldn’t have stayed away forever. She describes him as a charismatic but not arrogant guy, a racer the fans have always loved because he has the common touch – and talent.

Motorcycle racers come in two forms, Ellis maintains, those with a modicum of talent who bust their butts to get better, and those who work hard but are gifted with “an amazing cerebellum,” the part of the brain that controls balance.

“They’re like a bird or a fish,” Ellis said. “They don’t have to think about it. They have an immediate natural reaction to balance themselves without having to think about it. It’s a lot like a dancer.”

While immensely talented, Linder has never been unbearable about it. Ellis says he’s likable and fun, and that goes a long way with fans and clients.

But he doesn’t have a lot of outsides interests beyond going insanely fast on motorized vehicles.

“It’s his identity,” Ellis said. “It is who he is. He doesn’t really know anything else other than riding or driving.”

Well, there is the mowing. Yes, Linder mows for a lot of widows in Columbus, mainly to keep busy.

Sure, he rises at 4 or 4:30 a.m. most days and works on his bikes in home workshop, but when he doesn’t have a driving school gig or a corporate coaching event, he’s got to fill those days.

Ask him what his other hobbies are, and Linder makes a zero sign.

“That’s my big problem,” he said. “What do I do when I’m done? I mow now. I don’t go to movies, I don’t go to games, I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I don’t go to bars. I’ve got nothing to do. I get bored like crazy. You see my woods here – there’s not a twig on the ground.”

Naturally, he pushes the riding mower to its limits.

“I mow fast,” he said.

Linder also rides a lot, having reprised his street bike collection. In his corral now are a 1982 Honda Ascot, a ‘78 Honda CV 750, a BMW Dakar, a 2000 Harley Dynaglide, a 2001 Harley Road King and a BMW R1200.

“I really enjoy the motorcycles today,” Linder said. “You know, it’s a full circle.”

At times, he reaches directly back to 1965, wearing a leather jacket he bought that year that still fits him. Linder has his own gym and keeps himself fit.

“I’m in extremely good health,” Linder said. “Inside, I’m like a 25, 30-year-old. No disease, no blood problems. I just broke too many bones. I have to take care of that shoulder and the neck problem.”

He went to Sturgis this summer, and he ventures out on local roads frequently, even after a hip replacement surgery on May 2.

“I had surgery, and two weeks later I was on my moped. Four weeks later I was on my motorcycle. Six weeks later I was driving a Formula 5000,” Linder said.

He’s also staying busy with the driving school. His goal in teaching inexperienced drivers with powerful cars is simple. As Linder says, “they have a checkbook, but they have no knowledge.” They do, however have the common sense to come to a driving school.

“My goal is to teach you something. I don’t want to make you a race car driver,” Linder said. “But maybe I’ll teach you enough to save your butt one day on the road.”

Some just assume that high-speed driving really requires no special skills.

“We all have a different level of self-conservation, I call it,” Linder said. Some people have it deeper than others, and that’s what determines how fast you can be. You need talent also.”

He’s taught hundreds, and that sense of self-preservation is key. His, obviously, is on the outer edge.

“I’ve got a lot of pictures of going over 200mph – I take it while I’m driving,” Linder said, showing a cellphone pic of a speedometer registering 207. “You try to teach people to drive at 200, they don’t realize how hard it is. No clue. You have to create a bond. They have to trust you; then you can push them out of the limit, the comfort zone.”

That’s really what Linder’s life has been about – avoiding that comfort zone.

“For me, being inactive is a death sentence,” Linder said. “I always said, ‘As long as long as I’m safe, I’m enjoying it and I’m fast, I’ll do the coaching.”